Christopher Knight is an idiot. I recently read his blog post on the LA Times website in which he criticizes Michelle Obama and the White House Office of Media Affairs for staging a publicity event at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. His criticism is based on the fact that the Met is the number two tourist destination in New York City and the First Lady’s visit will do little “for the struggling arts infrastructure elsewhere across the nation, which doesn’t rely on tourist hordes.” It’s weird to me that an intelligent person, which I assume Knight is, wouldn’t realize that Michelle Obama’s visit to the Met isn’t really to drum up dollars for arts infrastructure (her visit and the money it raises isn’t going to make or break the Met or any other art institution), it’s to give a general sense that art is important and vital to everyone in the country who isn’t a part of the LA/NY artworld. Her visit is for the mom in Iowa who, because she thinks Michelle Obama is a good mother, a snappy dresser and an all-around strong female role model, might decide to take her kids and her money to the Des Moines Art Center one Saturday instead of to “Transformers 2.”

Knight’s post casts light on a situation in the U.S. in which political liberals have been divided from the intellectual left for a long time. I know most liberals in the art community voted for Barack Obama and I’m sure quite a few made donations as well. I’m less sure about how many went door-to-door to register voters or made phone calls for the Obama campaign. And that might be generous. There was probably a sizable number of pseudo-Marxist 20-30-somethings who, while reading their Foucault for Dummies, so internalized his assertion that “to imagine another system is to extend our participation in the present system,” that they just decided to get all punk rock and opt out of electing the one nominee in recent years who seems to have the balls to initiate substantial groundwork for health care and public education reform.

A radical theory: The United States has been getting more progressive and liberal since its founding and the rightly abhorred Bush presidency was a fucked-up anomaly that should have never happened. Al Gore won the 2000 election, the court system failed as it often does and for eight years the American citizens were pounded in the face with an unexpected barrage of sadistic mind games in the self-serving interest of a few greedy, corrupt lunatics. The U.S. Presidential timeline should read: Bill Clinton – Al Gore – Hillary Clinton. We would likely already have some kind of health care reform, a liberal Supreme Court and a lot more arts funding. The Bush Administration and their borderline-fascist policies have been particularly effective in blinding the artworld to the overwhelmingly progressive evolution the United States has made toward becoming a more free and just society.

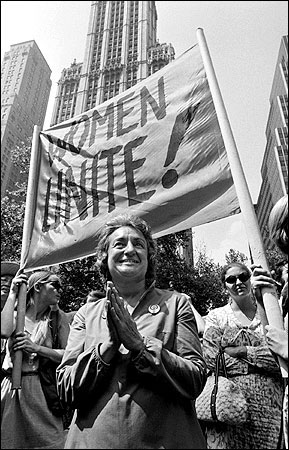

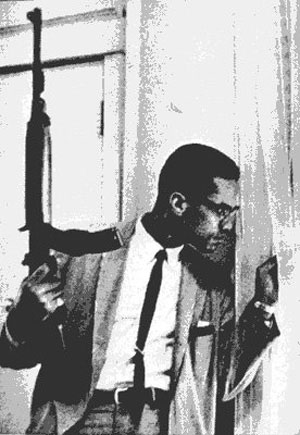

As a country, we have been good at recognizing oppressed people who have campaigned for constitutional rights. We outlawed slavery, we answered the civil rights call, the role of women as equal participants in our cultural and economic structures has slowly but steadily evolved and the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender movement is finding support. None of these problems are solved. An overwhelming number of black people are still enslaved in most American cities by poverty, women continue to be treated unequally and while basic economic and social rights for LGBT citizens seem to finally be seeing the light of day, the road ahead, as seen in California, still seems long. But the effort by the liberal left to change these situations seems steady and constant. We’ll always be able to imagine a utopia where society is more just and people are more free but it will always be just out of reach. It’s a goal continually in the making. The last eight years has made us forget that rather than becoming more culturally oppressive, our country has become more accepting. It’s not where I or any other self-respecting liberal would like it to be, but neither is Rome burning.

In its general acceptance of multiple viewpoints and appreciation for various cultural perspectives, the artworld has done a good job of internalizing the lessons of philosophers like Foucault and Marx. But many parts of the artworld have grown accustomed to the dismantling of linguistic, political, institutional and critical systems simply for the sake of demonstrating that everything is deconstructable. How else to explain a theory of art complete with its own special cadre of artists which proposes that only certain kinds of art are relational when, if you take Derrida and Foucault seriously, you understand that you don’t have to serve soup to Mary Boone in a Chelsea gallery to realize that all art is relational. The problem, as in politics itself, is that an infrastructure has grown up around the business of art-as-deconstruction. There are galleries, not-for-profits and residencies that have built their existence around a specific, theoretically-motivated art that has as its reason for existing the deconstruction of just about any idea it lays its beady little brain on.

When it comes to the artworld’s responsibility to its society, call me a cynic, but I don’t believe that making art, redefining vocabularies or offering up critical explications of the commodity object is going to do much to stop the population explosions in Indian and Brazilian slums or help strengthen labor unions which have been consistently battered by conservative legislation. I’ve been dragged kicking and screaming into the belief that the engine of art is economic. Only when we are bourgeois enough as a society to have the time and money to read a novel or visit a museum are we able to allow art to mean anything. So for art to become a place where meaning is born for everyone and not just an elite or lucky few, the first priority should be politics that results in decent legislation.

It’s much easier to sit in a studio in fancy tennis shoes and skinny jeans making ugly sculptural installations that “traverse subjects through the deliberate making of a fractured, non-hierarchal logic system” and count that activity as political action than it is to pass out fliers in a ghetto with the blue collar plebes that make up the actual political left in this country.

Heidegger, Derrida and Foucault are amazing writers and their work has contributed, at least for me, to a more satisfying understanding of the world in which I live. They have allowed me to think that once we understand the machinations of institutions and essentialist beliefs we are not left hopeless, but are left in a better position to change those institutions and beliefs. They’ve helped me understand that there’s no contradiction in thinking that the truth isn’t out there while still holding on to political hope. We in the artworld find ourselves in the position of deciding whether we should continue to believe in the activist model of liberal, social democracy or retreat to an academia that, despite a genuine interest in changing the world into a less oppressive place, seems to be increasingly isolated from the oppressed. The dirty little secret about the intellectual left and its appreciation of the helpful belief that there isn’t really anything we can point to and say, “this is the one and only final truth,” is that it doesn’t prevent you from being a prick, a dilettante or a fascist dictator.

It’s very possible that our liberal concepts of freedom and justice will finally buckle under the strain of diminishing resources and war-crazed politicians who do the bidding of the super-rich. But it’s equally possible that by continuing to try to actively shape our government and our society through concrete, incremental political action we may arrive at previously unforeseen solutions to problems that right now seem too large to understand, let alone solve. I do not believe that making art is enough. It’s not enough to make symbolic gestures or post an article on a website. I haven’t done enough to change my world and the last year has found me realizing that I still believe that we can make the world a better place and that I owe more to my society than I have been willing to give.

Michael Bise is an artist living in Houston.