Over the past week, a series of events has unfolded that brings into question what rights artists have, how they are protected, and who is responsible for enforcing them. In a sense, this particular situation has been a sort of case study, where the idea of unbridled expression is put up against moral responsibility, with institutions hanging in the balance.

In mid-August, Arts Fort Worth, a nonprofit organization that is partially funded by the city and operates the Fort Worth Community Arts Center (FWCAC), launched an open call for Further Fringes, a complimentary program to the annual Fort Worth Fringe Festival, which itself is a two-day event of performances hosted in the center’s theater spaces. Further Fringes sought to additionally activate the center’s gallery spaces with performance art works.

Local artist Sophia del Rio (disclosure: who previously has written for Glasstire, including about an exhibition at the FWCAC) was eager to submit a proposal for her first foray into performance art. The proposal, titled White men who paint landscapes are not artists, explained that in this experimental piece, Ms. del Rio would cut up a landscape artwork with scissors while discussing the history of landscape painting. She would then collage pieces of the landscape on top of a pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey game as a political statement about the history of colonialism in the U.S.

In her proposal, she wrote, “I have done research on how early map makers and explorers used artistic renderings of landscape to show what was being discovered and take images back to royalty in Europe during inquisitions, and early exploration of the Americas. The landscape tradition continued with early settlers moving Westward, paintings were turned into etchings and printed in newspapers.”

Ms. del Rio went on to explain that contemporary landscape paintings are still used as a way to showcase wealth. Additionally, she drew connections between colonizing practices and the recent issues that Arts Fort Worth has faced (the uncertain future of its building), as well as the increasing cost of land and housing in the city.

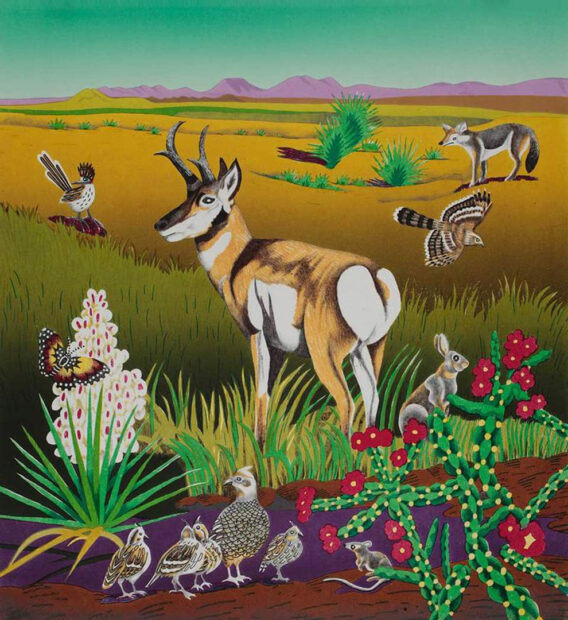

Ultimately, Ms. del Rio’s proposal was accepted, along with about a dozen other performances by local artists. Further Fringes took place on Saturday, September 9. What was not stated in the proposal, and what came to light during the performance, was that the landscape she would cut up was by another local artist, Billy Hassell, who is known for his depictions of Texas scenes and wildlife. According to Mr. Hassell, neither he nor his galleries knew his work would be used for the performance. Arts Fort Worth confirmed to Glasstire that its staff was aware Mr. Hassell’s work would be used prior to the performance taking place.

In a speech she made during her performance, Ms. del Rio drew a connection between early Texas landowners who acquired large tracts of land through policies related to westward expansion and those who now have the ability to sell their land to the state to be incorporated into the state parks system. She noted that while these landowners may view themselves as conservationists and environmentalists, they have used the land to earn a profit. This concept directly relates to Mr. Hassell’s artwork that was cut up during the performance: a print, from a larger series of works, whose sales help raise funds for the Texas Parks & Wildlife Foundation.

The week after Further Fringes, ephemera from each performance was installed in one of the galleries at Arts Fort Worth, including Ms. del Rio’s collages. One work features a donkey-shaped cut-out of the print affixed atop the pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey background; the other contains fragmented leftovers of the cut-up print, along with an invoice documenting its purchase from Houston gallery Foltz Fine Art. Arts Fort Worth told Glasstire that within days of the ephemera going on display, Anne Kelly Lewis, the Director of William Campbell Gallery, raised concerns that the performance degraded and destroyed the work of another member of the Fort Worth art community. Following further conversations between Ms. Lewis and Arts Fort Worth Exhibitions Manager Robert Long and Director Marla Owen, on Friday, September 15, Ms. Owen made the decision to remove the artwork from the gallery. Mr. Long was instructed to remove the work and contact Ms. del Rio.

After hearing about the removal of her work, Ms. del Rio contacted Wesley Gentle, the Executive Director & President of Arts Fort Worth, and made social media posts alleging censorship of her work and also alleging that “Anne Lewis threatened to sue the Community Art Center because Billy Hassell’s feelings were hurt.”

William Campbell Gallery provided the following statement to Glasstire: “There is no basis for the claims that William Campbell Gallery or its representatives (Gallery Directory, Anne Kelly Lewis) requested or demanded the removal of artwork. William Campbell Gallery and its representatives are opposed to censorship and firmly stand up for artists’ rights. The decision to remove [Ms. del Rio’s] work was solely that of Arts Fort Worth. Any questions or concerns regarding this decision should be directed there.”

Arts Fort Worth told Glasstire, “Arts Fort Worth works hard to create and preserve an environment where the freedom of creative expression can thrive in Fort Worth. Censorship is never our intent nor our policy. Encouraging a supportive and collaborative artistic community is also critical to our mission and we aim to respect the opinions and voices of all artists, including del Rio.” The organization also noted that it was not aware of any threat of legal action from Ms. Lewis, William Campbell Gallery, or Mr. Hassell.

Arts Fort Worth does have a history of supporting art about tough subjects. Earlier this year, Fort Worth Council member Michael Crain received a complaint from one of his constituents regarding a work of art on view in the organization’s outdoor sculpture gallery. Mr. Crain forwarded the complaint to the council member of the district in which the center is situated. The sculpture, by Sarah Ayala, titled Fuck the supreme court, is a large-scale polyhedron with some sides covered in repeating, simplified shapes representing female reproductive organs, and other sides with text related to abortion statistics, such as “About 1 in 4 women (24%) will have an abortion by the age of 45.” The piece was commissioned by Arts Fort Worth, after the organization learned that Ms. Ayala was planning to paint abortion rights murals in protest to the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision overturning Roe v. Wade. Mr. Long reached out directly to offer Ms. Ayala a spot in the sculpture gallery for a work on the same topic. Despite the complaint, Arts Fort Worth kept the artwork on view through the duration of its intended display.

Regarding the work by Ms. del Rio, on Monday, September 18, following a leadership meeting and a review of its policies and procedures, Arts Fort Worth determined that, “it was inappropriate to remove the work and also to not communicate with the artist prior to the removal.” The organization reinstalled the artwork, and it will remain on view through the end of the exhibition on September 30, as originally planned.

Mr. Gentle told Glasstire, “We regret the decision to remove del Rio’s piece and we did not communicate with her in a way that she deserved. We apologize and appreciate the opportunity to reevaluate our policies and procedures. We also extend our apologies to Billy Hassell for the way his work was represented without his prior knowledge. As with all art in the galleries, the work does not necessarily reflect the views of the staff of Arts Fort Worth.”

While the decision to reinstall the work at once validates the initial claims of censorship and corrects what could be seen as a hasty action of removal, the action of cutting up an artist’s work has potential consequences.

Ms. Lewis explained, “The concerns discussed with Arts Fort Worth were specific to the violation of VARA (Visual Artists’ Rights Act of 1990/91) — when an artists’ work is destroyed without that artist’s consent. I did not request nor threaten. To the contrary, I explicitly stated that I’m opposed to censorship and firmly stand up for the artists’ rights.”

In 1990, Congress passed the Visual Artists’ Rights Act (VARA), which was the first federal copyright legislation to provide protection to “moral rights.” Specifically, VARA grants the author of a work of visual art the right to:

– Claim authorship and prevent the use of his/her name as the author of anything that he/she did not create.

– Prevent the use of his/her name as the author of a work that has been distorted, mutilated, or modified in a way that would be “prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation.”

– Prevent any intentional distortion, mutilation, or modification that would dishonor the author.

Exceptions to VARA include the inherent modification of an artwork caused by the passing of time and by conservation or presentation-related issues, such as lighting and placement. An additional exception is if the artist gives written permission for the destruction of the work. These rights are granted for the duration of the life of the author.

Perhaps the most well-known example of an artist’s destruction of another’s work, with permission, is Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing. The piece was created in 1953, after Mr. Rauschenberg approached Mr. de Kooning for a work of art that he could erase. Mr. de Kooning agreed, and provided Mr. Rauschenberg with a drawing.

A more contemporary example of a modification and destruction of a work of art without the original maker’s consent is Ai Weiwei’s Colored Vases and Dropping A Han Dynasty Urn. As early as 1994, the artist painted a Han Dynasty urn with a Coca-Cola logo, and later he would continue to paint ancient urns in an array of vivid colors, thus essentially “modifying” them. In 1995, he photographed himself casually dropping another ancient urn, which, one could argue, is a destructive act that “mutilated” the original artwork.

Upon explaining her perspective on the act of cutting up Mr. Hassell’s print, Ms. del Rio claims, “I did not destroy the lithograph… I recontextualized the work into a larger conversation. My work is not about Billy Hassell. My work is a call to all artists working in the Landscape Genre to be aware of the colonial roots of this genre and do better.” Mr. Hassell’s name is not mentioned in the label text or title for Ms. del Rio’s work, though his signature is visible within the scraps of the cut-up print. It is fair to say that Mr. Hassell’s print used in the piece, as pictured above, has been damaged beyond potential for repair.

For his part, Mr. Hassell told Glasstire, “The manner in which [Sophia del Rio’s piece] was done was inappropriate. I think if the work had been acquired in a legitimate way and she wanted to do a performance art piece and use one of my works of art, it would have been different if she had asked me. I think it’s the manner in which it was done, not the nature of it, because I don’t think anybody wants to be construed as being opposed to freedom of expression. It’s absolutely her prerogative to express herself any way that she wants to. It’s just that if it’s done in a way that involves violating VARA, violating the laws that protect art, if the work was acquired in a fraudulent manner, if gallery owners and possibly the Fort Worth Community Arts Center was deceived in some way… those are the issues that I think take away the credibility of the performance of this particular artist’s expression.” A contextualization of some of Mr. Hassell’s claims in this statement are discussed further below.

To Mr. Hassell’s point, it would have been entirely within reason for him to expect Ms. del Rio to reach out and discuss her performance plan because the two have known each other for a decade. Mr. Hassell explained that he met Ms. del Rio in 2013 and that they have been in contact over the years in a professional context. For example, in 2021 Mr. Hassell wrote a recommendation letter for Ms. del Rio in support of her application to a graduate program in North Texas.

Glasstire asked Ms. del Rio why she did not ask Mr. Hassell for his permission to cut up his print or tell him about the use of his work. This would have been easy, considering she had included him in correspondence about the shipping and delivery of the work after she purchased it. Ms. del Rio responded, “I, and any other artist, who is using a work in a piece as criticism or commentary, does [sic] not need to request permission to use another artist’s visual imagery, as per the Code of Best Practice and Fair Use: Artist [sic] may employ fair use to build on preexisting works to provide social commentary.”

However, the background of Ms. del Rio’s use of one of Mr. Hassell’s prints is complicated further — a situation Mr. Hassell alluded to in his above statement. In August, Ms. del Rio reached out to Foltz Fine Art in Houston about purchasing the lithograph, titled Pronghorn. According to correspondence between the gallery and Ms. del Rio reviewed by Glasstire, an invoice for Pronghorn print number 17 of 30 was sent to Ms. del Rio on August 16, and the artwork was shipped soon after. Ms. del Rio contended at the time and still claims that the initial print she purchased never arrived. When she let the gallery know she had not received the work, the gallery, according to its correspondence and records, apologized for the shipping issue and had a second print (edition 4 of 30) from the same series hand-delivered to Ms. del Rio on September 5.

The correspondence also indicates that FedEx initially reported that the first package had been delivered to the wrong address, so the gallery opened a claim with the company to investigate the delivery. This week, FedEx closed the claim after determining that the package was in fact delivered to the address provided by the gallery, which was Ms. del Rio’s home address.

Upon learning about the use of Mr. Hassell’s print in Ms. del Rio’s performance, Sarah Foltz saw a photograph of the ephemera installed at Arts Fort Worth and noted that the print that had been used in the performance was edition number 17. (The hand-written number is visible in the top left corner of Ms. del Rio’s work, on what was the bottom left corner of the print). Additionally, the invoice from Foltz Fine Art, which is included in Ms. del Rio’s collage and dated August 16, says that the edition purchased was number 17, the original edition the gallery claims to have sent to Ms. del Rio.

Based on the gallery’s records and FedEx’s subsequent investigation, which were reviewed by Glasstire, it appears that Ms. del Rio paid for a single print, totalling $2,541.75, but ultimately received two prints: edition 17, which the gallery first mailed (and was initially flagged as lost, but was ultimately used in her performance and also marked as delivered by FedEx), and the second, replacement work, edition 4, which was delivered to Ms. de Rio by a courier. The August 16 receipt Glasstire reviewed from the gallery matches the one displayed in Ms. del Rio’s collage at Arts Fort Worth.

For her part, Ms. del Rio told Glasstire, “The Foltz Gallery was unable to deliver the work I purchased originally… I have, in an email from Sarah Foltz, that FedEx delivered the work to another address with no signature required. It was simply left at some random person’s door.” According to the gallery, this is the communication that prompted them to open their FedEx investigation into the allegedly missing print, which has since indicated it was correctly delivered.

Following legal advice, Ms. del Rio declined to comment further about the situation around her buying and receiving artwork from Foltz Fine Art.

In regards to artists’ rights, it seems that what happened to Ms. del Rio’s performance ephemera at Art Fort Worth could be construed as censorship: her work was removed because it was seen as inappropriate. However, upon further consideration, the center reinstalled the work. If flag burning can be a form of symbolic speech covered under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, then might Ms. del Rio’s modification of Mr. Hassell’s work be covered as well?

A potential unresolved issue in this situation is that what happened to Mr. Hassell’s print could be seen as a violation of VARA, as his original work was modified and presented in a way that links his name and work with violent colonialist practices which he does not connect to his own work. Furthermore, the question comes into play of how the cut-up print was acquired: if it was paid for appropriately, then is Ms. del Rio’s performance piece and subsequent ephemera also covered by VARA? There is no clear answer to these questions, and there likely will not be unless legal action is taken and seen through. For now, Ms. del Rio’s work will remain on view at Arts Fort Worth through the end of this month.

September 28, 2023: This article has been updated to reflect the fact that Arts Fort Worth’s staff did know that Ms. del Rio planned to use Mr. Hassell’s print in her performance prior to the performance taking place. However, neither Mr. Hassell nor his galleries were aware that his work would be used.

This article has also been updated to reflect the fact that Ms. del Rio did not specifically confirm with Glasstire the number of Mr. Hassell’s prints in her possession.