When the art collective HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN?, also known by the shorter form Yams, withdrew from the Whitney Biennial in May, the Whitney went from featuring a collective with thirty-eight black artists to scarcely any black artists at all.

Pedro Vélez, who participated in the Whitney this year as an artist/critic, is angry about the situation that facilitated the Yams group’s withdrawal, and he’s come to Oliver Francis Gallery in Dallas to present his thoughts on the matter.

The Yams collective withdrew in protest over the work of another Whitney artist, Joe Scanlan. Scanlan created a character named Donelle Woolford over a decade ago. Ambivalent about some collages he had made, Scanlan lit on the idea that inventing a new creator would bring the collages into their fullness as works of art. He decided that the creator ought to be an African-American woman. He named her after a professional football player and invented a biographical sketch. Although it has always been a rather loose secret that Woolford is a fiction created by Scanlan, Scanlan has been submitting work as Donelle Woolford for a while. The 2014 Whitney exhibition catalog shows a bio of Woolford and credits her as responsible for the piece titled Dick’s Last Stand, which is the work that upset the Yams group. In it, the artist Jennifer Kidwell portrays Woolford performing a Richard Pryor routine. The video below is from a “Dick’s” performance in February at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit.

Hyperallergic published a statement by Sienna Shields, a member of the Yams group and director of the video Good Stock on the Dimension Floor: An Opera, which was the Yams’ entry in this year’s Biennial. Here is an excerpt from that statement:

“We’re sure that we don’t need to explain how the notion of a black artist being ‘willed into existence’ and the use of a black FEMALE body through which a WHITE male ‘artist’ conceptually masturbates in the context of an art exhibition presents a troubling model of the BLACK body and of conceptual RAPE. The possibility of this figure somehow producing increased ‘representation’ for black artists both furthers the reduction of black personhood and insults the very notion of representation as a political or collective engagement.”

You can see the statement, in full, here.

Rape is a potent word. There is no legal definition of “conceptual rape,” and it is not clear whether Shields means that Scanlan is a conceptual rapist for inventing the persona of an African-American woman and fulfilling that persona through another artist who is an African-American woman; or whether Shields means that any writer or director of one race or gender is a conceptual rapist when he or she creates a character of another race and/or gender.

Also, there is this: in her essay “The Rape of Narrative and the Narrative of Rape,” the cultural theorist and video artist Mieke Bal, writing about the Biblical book Judges, follows a theory that rape in that book is the narrative form chosen for revenge of an old institution over a new. I doubt that Shields is referencing Bal’s essay, but it is worth considering that the concept of rape as revenge, old against new, has something to do with Shields’ accusations. In this case, I don’t mean that the old institution is one of racism or misogyny. I mean the old institution as a form of white liberalism that perceives itself the charitable platform upon which people who are not white, not male and not heterosexual may gain a proper hearing. Perhaps the accusation here is that the form of white liberalism that initially inspired Scanlan to explore selfhood, race, and gender by creating the Donelle Woolford persona has lapsed into an old institution, one that menaces the new institution of minority groups that believe a white male go-between isn’t necessary to legitimize their messages to the public.

Looming inscrutably over everything is the Whitney Biennial itself. Love it or hate it, the Biennial remains an influential survey of American contemporary art. And yet, what gets in is often a source of surprise and controversy. It has been strongly criticized in the past for favoring white male artists over women artists and artists of different races. And its rank as a high spectacle makes it impossible to divorce marketplace calculations from the creativity and the controversies of the artists involved.

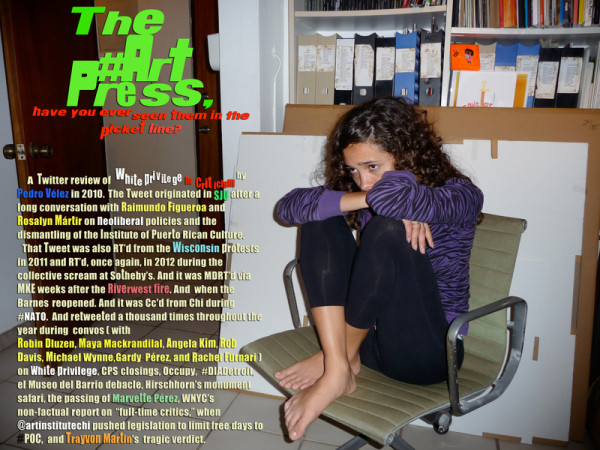

Pedro Vélez’s project at the Whitney Biennial included “visual essays,” which emulated movie or pop music posters. Vélez overlaid quotations by art critics onto images depicting art world figures. He also wrote reviews of the Biennial on postcards, sometimes making scathing statements, that he freely distributed at the event.

Vélez’s work at Oliver Francis Gallery has a simple aesthetic: angry and loud. He uses the words “corrupt” and “monochromatic” to describe a white majority in the art market. However, the effect of Vélez’s angry phrases is diminished by his reliance on insider art talk and pop culture. Take for example his sick or narcotized Twitter bird. He distorts the familiar social media symbol, implying that we are all unwell and zombified by our reliance on communication technology. Sure, the affected Twitter symbol is funny, but his point is undercut by Vélez’s own relentless use of Twitter. Investigate him online and you will find a dedicated user of social media. Even the language of his Biennial reviews has the familiar staccato of one who composes while counting characters of text. Lyricism and complexity are absent. There is no insight from this Whitney insider, only yelling.

Vélez’s problem is that he looks to the art market as high judicial ground, rather than searching his own conscience and experience for the immediate and searing truth he feels charged to reveal. He can never be wrong in his arguments about the reductive effects that race and sex discrimination have on U.S. culture. But he’s chasing a chimera in the art market. He holds too fast to the idea that the only way to compete with the glossy art coverage he feels is marginalizing non-white male artists is to create works in the same style. Even the graffiti-style element in his mural at Oliver Francis Gallery seems perfunctory: there is the sense that he feels an obligation to perform in that medium.

I’ve written before about a troubling trend in post-modern art, this business of trying to critique a society reliant upon commercial spectacle by using the tools of commercial spectacle. To rehearse it quickly: The business of fighting spectacle with spectacle is neither illuminating nor transformative. It is only a surface response and lacks for subversive ideas that might upset the status quo and present alternative points of view.

To put it another way, if I make a drawing, then I am, in a sense, committing a political act. I’m communicating to my managers that, at that moment, I am not being managed; I am revealing an aspect of my own conscience in an improvisational way. If I invest my drawing with the authority of my managers, by, say, keeping to the middle-of-the-road expectations of advertisements and the familiar terms of social media, then I am turning myself over again to the status quo. I have not left the norms of control even though the original intention of my drawing was to carry myself past those parameters.

Art is as much prophesy as it is anything else. Past traditions are searched for oddities and truths that may seem relevant or even new in the present light, and then that light is cast forward to offer a glimpse of things to come that one can hope for, or fear. An aesthetic that is built on the acceleration of messages found on social media and not on reflexivity —the excavated sensibilities of the artist — lacks any sustained power over the imagination.

I point to Kara Walker as an artist whose fascinating forms of protest are linked with a heady cosmology. Walker is aware that the so-called masterclass of the antebellum South took very seriously the ideas about patriarchy and increase they found in the Bible. The patriarch believed himself to be charged by God to lead as many people as possible down the righteous path and to dominate the landscape with with crops. The patriarch felt he would perish, have his life extinguished by God, and maybe suffer Hell if the crops didn’t make and the flock of souls he tended — women, children, slaves — didn’t embrace the ordering principles of religious life. And Walker is aware that the aspect of Christianity that inspired enslaved Africans was the coming of an eschatological event, a leveling experience that would cut the masterclass to size, to be followed by an act of judicial grace, in which the patient and humble would gain power and the greedy would know humiliation and shame. Walker’s art searches the truths and oddities of these traditions, which is why her work recalls the antebellum South, but also suggests a strange sort of spiritual warfare, and at the same time flashes on startling images of present and future U.S.A.

Walker is but one example of an artist who uses the reality of racial differences (the history of atrocities and coexistence) and fantasy to create a prophetic sort of art work. Velez’s commentary, by comparison, lacks rigor.

It’s good that Dallas is being given an insider’s point of view of the latest Whitney Biennial controversy. We have Vélez’s emotional take on the matter, but nothing that examines the complexities of selfhood, race and ethnicity. The work lacks enough depth and weight to be transformative. It is easy — in this country, at this time — to voice dissent. What is truly troubling is the number of artists who voice dissent through the means of the status quo, rather than searching their own identities, experiences and traditions to lengthen ideas beyond that scope. If the mold is too limited, break the mold.

The Pedro Vélez mural/critique is on display at Oliver Francis Gallery through June 7. Oliver Francis Gallery, 209 S. Peak St. Dallas, Texas 75226, +1 817 879 8231, www.ofg.xxx