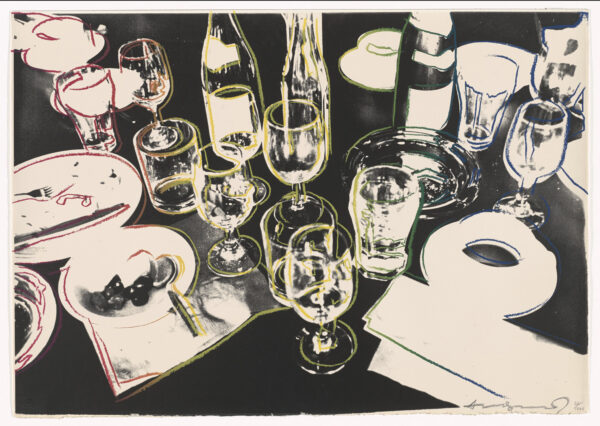

After the Party, a 1979 screenprint by Andy Warhol (1928-1987), draws our eye to the remains of what must have been a raucous dinner party. Laid out on a sprawling table, we see empty glasses, dirty plates, champagne bottles, and a half-eaten dessert. Due to the out-of-focus, overexposed photographic imagery, these objects appear silhouette-like and ethereal, bleeding together through their lack of contouring. Around the lips of glasses, hand-painted lines in rainbow colors — magenta, orange, yellow, lime-green, indigo — jitter with life.

Warhol’s chance-based process allows for such looseness of technique. But these brilliant colors also suggest the glittering, mosaiced surface of a disco ball. Given Warhol’s legendary status as a socialite, we can assume the scene was once populated with members of his Factory entourage, now en route in downtown New York. In this multilayered way, the print subversively bridges fine art, nightlife, and dance culture, all linked to New York’s queer community.

The current exhibit at the Art Museum of South Texas (AMST), Warhol, Johns and Stella: Revisited, is full of such world-making artworks, many of them with a decidedly queer sensibility. A “remake” of the 1972 exhibit, it features the same trio of visual artists who helped inaugurate the opening of Philip Johnson’s iconic addition to the coastal museum. This iteration aims to revisit the formalistic concept of “the artwork in a series,” as in the 1972 edition.

However, I claim that a more interesting story is buried in the selection of art pieces. Spread across three galleries in the Miller Building, the pieces by Warhol, Frank Stella and Jasper Johns reveal Modern art’s various connections to the queer community and dance community, through color, design, and subject matter.

Warhol’s early career in advertising — where he produced seductive images of products — laid the groundwork for the visual signifiers of his sexual identity. The artist’s novel blend of commerce and queerness is reflected in several Pop prints on display, such as Dollar Sign (1981); the charming cat portrait, Sam (1954); and Flowers (1964), a series of lithographs based on an appropriated photo of hibiscus blossoms by Patricia Caulfield.

After leaving his hometown Pittsburgh and relocating to New York City in 1949, Warhol’s passion for queer iconography bloomed, most famously in silkscreen portraits of drag queens and trans sex workers, such as Ladies and Gentlemen (1975), a portrait of Stonewall Riot heroine Marsha P. Johnson. His obsession with the modern dance community developed concurrently, from his early illustrative work for Dance Magazine in 1951 to his enthusiasm for attending Judson Dance Theater performances featuring Fred Herko. AMST’s selection of prints convey Warhol’s queer sensibility, obliquely, without calling attention to it. This is a curious curatorial elision given Warhol’s recuperation as a gay art-world icon in a Netflix TV series (The Andy Warhol Diaries, 2022) and recent exhibitions such as Femme Touch (2020-2021) at the Andy Warhol Museum, which centered on the women, femmes, and nonbinary individuals in the arts who were intertwined with Warhol’s life and career.

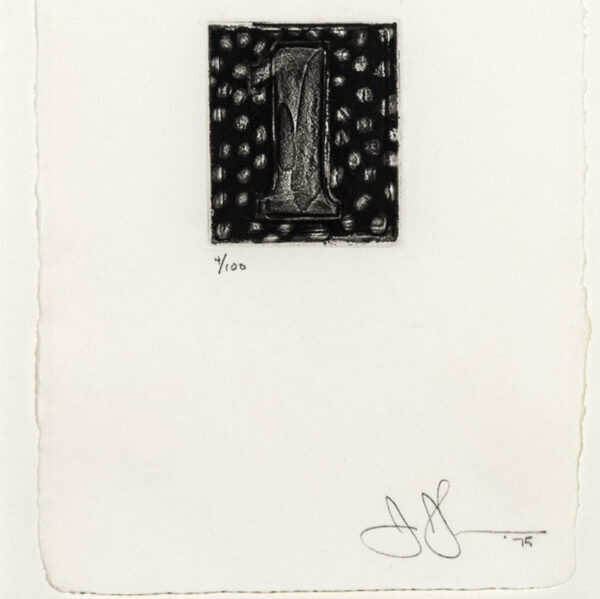

Like Warhol, the art of Jasper Johns (1930-) is infused with references to queerness and professional linkages to the dance world, but the show largely leaves these connections implicit. The worlds of modern dance and queer sociality collide in otherwise abstract pieces in the show, such as within 0 Through 9 (1979) by Johns. This series of monochromatic etchings is initially unassuming. Each work centers on a single number (0-9), decorated with scratches, dots, doodles, and embellishments that hover between improvisation and order. Arranged in a countdown formation on the gallery wall, the pieces suggest the repetitive timing and rhythm patterns used by dancers to match music. Forcing the viewer to swing back and forth from piece to piece, they haptically approximate the diverse institutional settings Johns navigated.

Johns, the American postmodern painter known for his interest in language, flags, targets and numbers, served as Artistic Director for Merce Cunningham Dance Company, designing sets and costumes for the famous choreographer. For six years, he was romantic partners with Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), at a time when it was illegal to be in a same-sex relationship.

The exhibit’s centerpiece is a trio of Frank Stella works — the fluorescent stripe painting Double Scramble (1968), the polygonal painting Moultonville I (1966), and the exploded mixed-media work Diepholz II (1982). This trio of pieces shows the painter’s disciplinary promiscuity, as he moved away from 1960s-era parameters of medium purity and optical flatness. For example, Diepholz II is a large-scale construction of shapes cut from aluminum paneling. Painted with flashy colors, geometric and curvilinear lines extend outward, vortex-like, pulling the viewer into a maze of pirouettes, ribbons, and wandering paths. Notably, Stella’s work in this period was criticized for being too “disco-like,” due to the artificial coloration and theatrical play of clashing forms.

In Double Scramble, a painting comprised of two sets of concentric squares, fluorescent alkyd paints index the artist’s creative interplay with modern dance. Before he made this painting, Stella designed the set and costumes for Scramble, a 1967 dance piece by Merce Cunningham. Stella’s set consisted of strips of canvas in the colors of the spectrum. Mounted on vertical frames, the canvases were moved around the stage by dancers who wore jumpsuits and tights. This “scrambling” of musical, choreographic and painterly practice is replicated visually in the double-paneled painting, as Double Scramble’s alternating bands of color push and pull at the viewer’s eye in pleasing, yet disorienting ways.

Stella’s boundary-crossing work is often said to have rehabilitated the “dead” medium of painting in the 1970s. Yet Stella may be more expansively understood, in this context, as a starting point for “social abstraction,” a term coined by LA-based painter Mark Bradford for a new type of visual art. Social abstraction does not retreat from the historical world, but rather pulls into itself multiple temporalities, materialities, identities, disciplines and ways of relating.

AMST’s modest show provokes rich discoveries such as these, inviting the viewer to linger a while and witness the connections lying in plain sight between modernism, queerness and multiple artforms in the late 20th century. However, the curatorial framework that the museum imposes on these objects is narrowly formalistic, tending to focus only on the artist’s contributions to their respective medium or corresponding “-ism.”

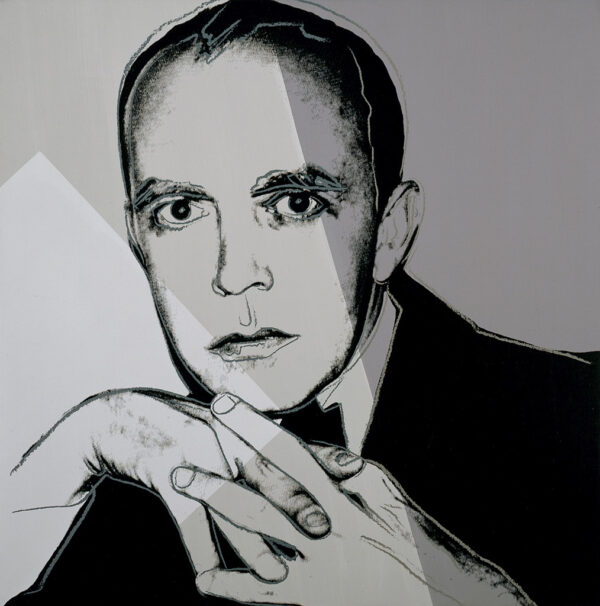

Nevertheless, key players in the show personally identified as queer or associated with queer communities, although not always publicly. David Whitney (1939-2005), the Guest Curator/Director of Exhibitions for the Art Museum in 1972, and museum architect Philip Johnson (1906-2005), were both gay men. Meanwhile, the artists fostered vital linkages to the dance world. Curiously, the exhibit passes over these connections in silence. Warhol’s 1980 screenprint David Whitney, a portrait of queer masculinity featuring flat tones, metallic flourishes, and swirling lines, forcefully brings out the contradiction between visible identities and artistic formalism at play in Revisited.

In a time of increasing political violence, it is damaging for the art world to deny sexual diversity while recapitulating formalist accounts of American art. Especially in conservative regions of the U.S., curators have a responsibility to identify and showcase the contributions of artists who belonged to socially marginalized groups. If the exhibit applied attention to forms of difference and interdisciplinarity, these works would more effectively allow us to imagine a revised history of art that is more inclusive and socially aware.

Warhol, Johns, and Stella: Revisited is on view at the Art Museum of South Texas through January 1, 2023.