The Whitney Biennial (and the Whitney Museum itself) has been dogged by controversy these past few years. Two years ago, the Biennial suffered a blow when artist and writer Hannah Black wrote an open letter against Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till — a quick and loose figuration of the young black man in his coffin — calling for its removal, and criticizing the artist for using the imagery of black death without fully encapsulating its meaning as a white woman. And if that wasn’t enough, that same year Jordan Wolfson presented a VR piece titled Real Violence (2017) — a work that invites the audience to bear witness to a very graphic violent scene where a bystander decides to beat the life out of a complete stranger with a baseball bat. The CGI scene caused an immediate uproar, and added to the overall disputes and polemics against the show.

It would seem that this year’s Biennial would be no different, considering the current outrage over the Warren B. Kanders debacle that started late last year. (Mr. Kanders is the CEO of the weapons manufacturer Safariland, and sits on the Board of Trustees at the Whitney.) After all, what is a Whitney Biennial without a little controversy? Well, perhaps it’s a modest curatorial achievement that deserves great praise, despite how unexciting it may be in the absence of public embroilment. And this year’s Biennial does just that, or at the very least comes very close.

Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta, the organizers of the 2019 Whitney Biennial, have accomplished something quite outstanding: a complex and richly diverse survey of American art today without the hitch of desecration or shock. Despite the Kanders controversy, Hockley and Panetta’s Biennial has managed to go nearly unscathed.

(Michael Rakowitz was the only artist to pull out of the show.)

Nevertheless, many critics of this year’s Biennial claim that the show went soft or played it bit too safe in order to avoid the “c” word. Linda Yablonsky mentioned in her review in the Art Newspaper that the Biennial “is missing a radical spirit.” Yablonsky goes on to mention that “[t]his exhibition tries to do it all, without actually making a difference.” This seems somewhat disingenuous being that this year’s iteration is the first to have a roster of artists where the majority is not white. And while much of the conversation around this Biennial is how young the artists are — more than half are under the age of 40 — not many critics have addressed the fact that half the roster identify as women, and that there is a huge inclusion of queer and transgender artists, as well as indigenous artists, Latinx artists, and Puerto Rican artists — another first for the Whitney.

The show quite radically responds to an effort to stretch the limits of what American art really stands for and looks like, and does so by including such a diverse group of artists. Take for example Las Nietas de Nonó, an artist collective comprising of sisters Lydela and Michel Nonó from Puerto Rico. The two present Ilustraciones de la Mecánica (Illustrations of the Mechanical), a collaborative performance that has seen several different iterations since 2016 — which was also presented at last year’s Berlin Biennale — and sees both artists stage a cryptic and yet poetic showing the horrid history of medical experimentation on Black female bodies in Puerto Rico. The work is a striking and welcome gesture advocating for reproductive rights of women of color.

Another is Laura Ortman, a Navajo violinist whose work in the show is not to be missed. A musician by trade, Ortman collaborated with dancer Jock Soto and filmmaker Nanobah Becker to produce My Soul Remainer (2017), a five-minute video depicting the artist playing the violin and Soto dancing before a southwestern landscape. The music is layered against various field recordings with sounds from various instruments. The result is an ambient and profoundly engaging piece of work.

What the show doesn’t offer are examples of highly politicized or agitprop work that is ubiquitous during the Trump era. (The only exception is Forensic Architecture’s Triple Chaser, a recent video that takes direct aim at Kanders’ possible ties to war crimes). In fact, this year’s Biennial is the first so-called “Trump biennial,” since the last one was organized prior to his inauguration. And despite all this, the exhibition is not a direct response to the Trump administration, but displays a great sense of quietude and discipline in regards to politics. There is an almost subtle subversiveness inherent in all the works in this year’s show.

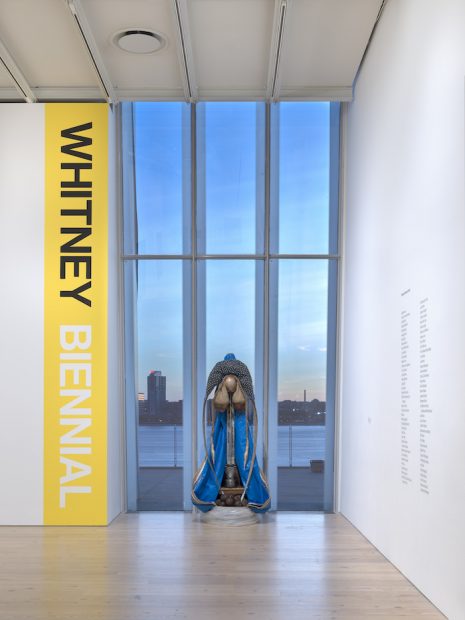

This can be easily seen in Alexandra Bell’s Friday, April 21, 1989 — Front Page (2019), a series examining how New York City-based newspapers covered the Central Park Five case in 1989, where five young men of color were wrongfully accused and convicted of raping a white woman jogging in Central Park. Bell’s work carefully highlights and redacts some of the language used in these periodicals that demonstrated the inherent biases that helped villainize the innocent boys. Similarly, Tomashi Jackson’s, Third Party Transfer and the Making of Central Park (Seneca Village – Brooklyn 1853-2019) (2019), a beautiful collage of rich color and abstract form made from detritus (newspapers, fabric, tape paper bags, etc.), endeavors to tell the story of the destruction of Seneca Village, a black settlement in Manhattan razed to make way for Central Park. And Daniel Lind-Ramos’s Maria-Maria (2019) [pictured at top], an assemblage sculpture made from materials that hark back to Hurricane Maria and takes the shape of the Virgin Mary, serves as a reminder of Puerto Rico’s history of colonial occupation.

This of course is only a sliver of what the Biennial has to offer. There are some great works from established artists such as Nicole Eisenman and Simone Leigh, as well as impressive works from upcoming artists Martine Syms and filmmaker Garrett Bradley. The contributions to the show are beautiful, smart, and enticing. And although they are not “in your face,” and perhaps on the surface absent of pointed political didacticism, they do pack a muted punch. This is quite refreshing when our current political climate is overrun by talking heads, angry tweets, and political grandstanding.

Through Sept. 22, 2019 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City