I struggle with Sterling Ruby’s work, but the struggle seems futile, given there’s so little to sink one’s teeth into. Expecting too much from him is like expecting nourishment from a Big Mac. Ruby makes cool-looking art, no doubt. Cool Shit. But I think his impulse is mostly limited to that — making cool-looking shit — and so I’m often mystified by his seemingly unchecked success. I tend to favor art that, even in the smallest gesture, can unfurl layers of nuance and potential interpretation. Ruby makes big things that are friendly, loud, un-tortured, and, I think, unintentionally dumb. The angst, or ‘angst,’ feels forced or piped in, as an afterthought. As mega-gallery, mega-collector material, his work isn’t particularly credible. I’m not buying it, in every sense of the phrase.

His current semi-retrospective of sculpture at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas is curated for maximum visual punch: the show is a muscular assortment of monochrome monoliths; drippy gothic things that tower over your head; jutting appendages and thick, glistening surfaces. Like craving McDonalds and a Katy Perry tune on a road trip, sometimes we crave the equivalent of junk food or a pop song from our art. Ruby fits that bill to a T, and this show is truly okay exactly on that level, at least while you’re surrounded by it. But its impact on your consciousness evaporates the second you leave the museum. That is, unless (like me) you spend the next three days trying to figure out why nothing about the show has stuck with you. I think the greatest hits of an artist who works this hard and attracts this much attention should loiter in your brain and soul for a while. They should upend your world at least a bit.

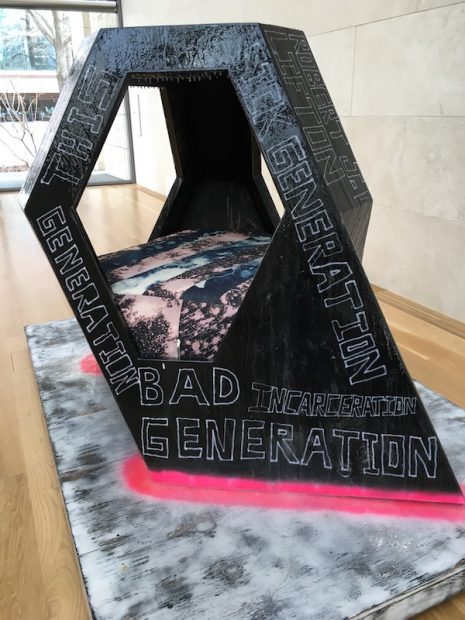

Ruby makes a lot of these big, now-famous things, but he has a tendency to undermine individual works with juvenile or ostentatious touches: dozy text additions to pieces that would be more open to layered or complex interpretation without it, or ‘ironically’ grandiose titles that undo whatever interest you were working up to when first encountering the piece. I was admiring a work in show titled Inscribed Monolith, from 2006, with its burnished white surface and a cheeky, messy graffiti scrawl of the word ‘orgy’ on one side — and I thought, Great, now we’re cooking with gas — but then I turned the corner and on the other side was the same cheeky, messy graffiti scrawl, but this one reads ‘jail.’ Really? ‘Jail’? Sad trombone sounded in my head. He blew it. No pun intended. Ruby is, after all, a skater-fashion-farmer-dude turned mellow LA artist whose brushes with the law are probably limited to parking tickets. Like I said, I don’t quite believe this guy, and I get no sense of what drives him, or haunts him, or electrifies him, other than a really admirable work ethic and a desire to please.

Here’s the thing about the best artists: I do believe them, in that I believe their work communicates even an unconscious consistency about them, body after body of work. Sometimes it’s exorcism, sometimes it’s a reckoning, sometimes it’s a way of ordering the world, or meeting it head-on with a massive, manifest force of ego. But they mean it. We know Mike Kelly was one of Ruby’s mentors. But I believe in Mike Kelly’s bristling and schizo-affected relationship to childhood, suburbia, and fantasy.

Each successful piece by a believable artist can stand alone in a museum and get a lot across. A whole show of works by a believable artist can be a psychological and emotional event. And it allows you to come to know something crucial about the artist, something that becomes familiar from then on, and tweaks your own view of the world (even if only) by a degree or two, and that’s a kind of baptism. Work doesn’t have to be political or fraught to make an impact. But it seems as though Ruby is trying to be political or fraught, and he can’t sell that shirt off his back, perhaps because that’s not who he really is.

I do like Ruby’s giant ceramic ashtrays — I see something human and circumspect in these heavy, cluttered, hand-worked vessels. They look like they stepped out of a particularly sardonic Guston painting, like animated Godzillas of clay that gleefully crap on your day just to keep you honest. I feel some compulsion and resignation from the artist in them. I also like Big Yellow Mama, a giant powder-coated aluminum chair installed outside that reads like an army of clean-but-monstrous Legos have assembled themselves, with Rietveld in mind, into a cheerfully sinister electric chair. It looks just like the kind of thing that I could have grown up seeing at NorthPark — the Nasher family’s other public gallery — and would have loved, and would probably have put my affection for Sterling Ruby’s name alongside those of Stella and Rosenquist. A single work by an artist can be magical. A lot of works by that same artist can unravel the mystery and undermine the oeuvre.

Perhaps that’s the one thing that will stick with me from this show: the big yellow chair is pretty great.

At the Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas through April 21, 2019