Every artist has a list of heroes—forebearers who’ve saved their ass in moments of doubt in the studio. My list is short, starts with Masaccio, and includes Rembrandt, Manet, and that beast Goya. But none of the artists on my list hold the emotional pride of place that Philip Guston does. Guston had his list too. He made a painting in 1973 that listed them: Masaccio, Piero, Giotto, de Chirico, Tiepolo. When I visited the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston recently to be abused by the dizzying terribleness that is Yayoi Kusama, I was happy to be greeted by three large, late Gustons newly installed in the lobby.

Guston is most famous to contemporary viewers (and an inspiration to a generation of painters who grew up on Beavis & Butt-Head) for his apparently radical shift from High Modernist abstraction to cartoony, socially charged symbolism. It’s a well-documented history and the catalog from the Guston show mounted in 2003 by Michael Auping at the Fort Worth Modern is a good place to start an investigation. Instead of presenting a capsule history here, I’d rather tell you why every time I see a Guston on the wall I have to stop and swallow the lump in my throat.

Art history is a little like the law. It offers an inventory of precedents that show what has been claimed as art and what has been rejected as fraud. Most of art history is made up of split decisions that lay dormant for centuries waiting for an artist to reinterpret them and unlock the hidden potential in their own work. The moments of doubt that cause artists to look for a light out of the dark make up a magic hour during which all of art history, every half-baked idea and long-dead ancestor, is electric with potential. After the death of my father my work soured. I was looking for a light and Guston set me on a path that has led to my work now.

Seeing the Gustons in the museum lobby came at a nice time. I haven’t made any work in six months and am just now getting back in. There’s nothing worse than being blocked in the studio. What can be a glorious, mythic battleground where aesthetic failure and triumph of will argue and produce a work of art that is a heady compromise between defeat and victory can just as soon morph into a stupid, boring room with concrete floors, interrogation lights and rat shit on the walls. Will we feel it today? Will the hours disappear in the thrill of knowing we’ve seized the thing by the tail? Will we pound our head against the wall all day, masturbate and anaesthetize ourselves with Netflix and wine?

It’s not an original idea, but for me Guston is Icarus. His body of work spells out a trajectory that begins with a leftist political consciousness in the days of revolutionary socialism when the exiled Trotsky spent time with Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, then climbs to the transcendent heights of Abstract Expressionism with its desire to dissolve the travails of human life into a gorgeous haze of ideals, and finally ends like a slip on a banana peel into a comic maelstrom of wrist watches, shields, hairy legs and always the insecure artist hiding under his comb-over. If Icarus had crawled out of the sea after the crash and made a painting, he might have made something that looked like Guston’s self-deprecatingly titled Legend with its horse’s ass sandwiched under the artist’s head and pillow like an irritating dream.

For adventurous artists there comes a time when the frame through which they view the world is completely knocked out of whack. If you’re lucky enough to experience this whiplash, don’t be afraid: the real work of building an artistic identity is just beginning. In his act of creating a second authentic artistic identity Guston has shown me, and many generations of artists, that losing faith in an idea of yourself as an artist doesn’t have to be the end. You can make art after disillusionment. That’s usually when things get really interesting. It’s the myth of the Phoenix and it can be real if you don’t lie to yourself in the studio

But Guston never exactly soared again after his disillusionment with abstraction. He died at 67 of a heart attack, collapsing in a psychological heap of heavy shoes, cigarette butts and empty liquor bottles. His late work was painted under the glare of the iconic single light bulb that had lit a dark closet in his childhood home where he began his journey as an artist. One of Guston’s last canvases, Untitled (Head), painted in 1980 depicts the lumpen, Cyclops profile that invariably represented his own puffy face at the bottom of a hill strewn with stones. At the end Guston wouldn’t even allow himself the comic glory of a self-portrait as Sisyphus. Instead he painted himself as the inert rock itself, unmoving at the bottom of the hill.

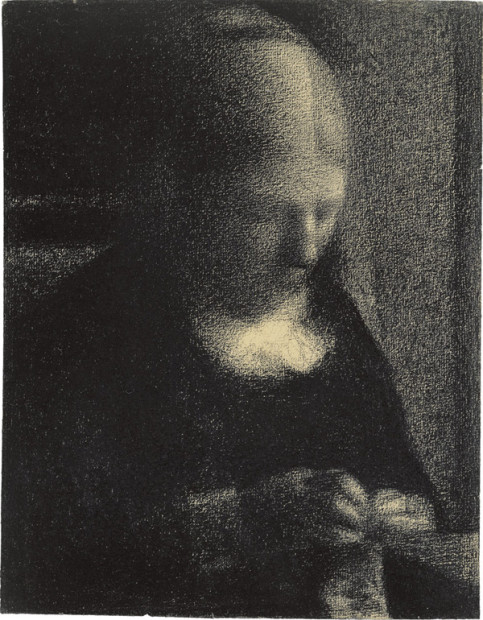

Guston’s late work is deep and rich with allusions to the entire Western canon of painting. They’re deceptively masterful and walk the line between tragedy and comedy like a standup with a complete understanding of the history of human civilization. But I can’t live in Guston’s world much these days. His monographs aren’t much help in my studio right now. But I’m glad he’s hanging out in the lobby. As I get back into my own studio it was a nice reminder that it’ll come back. The waters aren’t as choppy this time and I’m looking for a softer light. Seurat’s drawings have a nice glow.