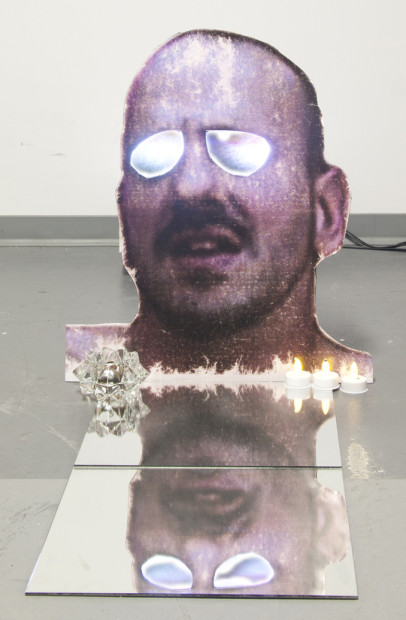

![AN ANDACHTSBILDER (PRYING PERCEPTION OPEN) [version 2], 2012 variable size, photographic print, resin, plastic crate, jewelry chain, colored lights, HD projector with no input source.](http://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/LOZANO_00-600x385.jpg)

Lauren Moya Ford: Does art have boundaries?

Ivan LOZANO: Art is suffering from an identity crisis; its boundaries have become porous after decades of annexing so many disciplines into itself. This gives us an amazing opportunity to redefine the field and re-draw its boundaries (or not), and to cut out what we don’t agree with. My background is in experimental film and video and, when I was in that world, the avant-garde was not just something that existed—it was almost an artist’s moral responsibility to be a part of it. I don’t agree with most things, and I’m not willing to take things as they are. I hope I can make people realize that our “moment” has a narrative, a context and a history to it—be it language, images, color choices, “gay culture,” technology, media or any other area of “knowledge.”

LMF: How does your work pioneer form and content?

IL: Artists have a responsibility to make sense of the disparity between technology and our understanding of the impact it has on culture. I’m just approaching it from the perspective of a middle class, queer, cisgendered male, Mexican American. I am part of the first generation that is native to the Internet but also remembers (although fuzzily) what life was like before. We’re living in a time when the technology we’ve created is changing so quickly it’s impossible to keep up with its effects. Almost every moment in our lives is governed by computer code. As I’m typing this answer on my keyboard, code that is too complex for any one human to understand translates my keystrokes into data displayed as pixels that show up on my laptop screen. I will then send this to you via email. By the time someone reads this on Glasstire, a ridiculous amount of complicated processes of encoding and decoding between computer languages has happened. It’s the same situation with images. Most of them are now, at some point or another, code. As we involve computers more and more in image creation, what we experience is not an indexical trace of anything, but a reification of an utterance in a mathematical language that we cannot understand. I can type a series of commands on my keyboard and I can manifest images, videos, sounds. These processes are occult, they’re magic.

(for full version visit http://ivanlozano.net/GIF/SUBROSA.gif )

LMF: Where does your interest in folk religions come from?

IL: From my love of science fiction and the occult. It was clear to me that, as Arthur C. Clarke wrote, “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” I also credit Cauleen Smith, my undergrad professor, for exposing me to AfroSurrealism. I wondered whether the folk traditions I remembered from my upbringing in Mexico could offer solutions to problems in technology. I was fascinated by the idea of Santeria rituals as computer code, or Orishas that could travel through cyberspace as ways to combat the dehumanizing side effects of digital revolutions. Folk religious traditions are a political tool and an “antidote” to the alienation that comes from living under Neoliberalism and Globalization.

LMF: How does magic play a part in your practice?

IL: It seems to me that for any artist, a certain degree of magical thinking is essential to cultivate. Magical thinking is the belief that your thoughts can have a physical effect on the world just by thinking them. It’s been shown that things like prayer, rituals, meditation or superstition can have meaningful psychological and physical effects on its practitioners. My particular brand of magical thinking considers each piece a spell, an incantation. Most of my work appropriates pornographic images or videos found online. Considering an image file pornographic means that something in the code of the image makes it so. If I convert the image-as-code into a print and cut it up or digitally manipulate it with software, then parts of that pornographic code are in my new file and its final physical iteration. What I try to achieve in my work is—more often than not without resorting to representations of sex or sexual organs—to actualize that eroticism by using abstracted bodies and cutting up code. To put it in magick terms, “as above, so below” (pun intended).

![MILAGROS I [detail], 2012, 48x17x17, resin cast of surgically reconstructed hand, metal pipe, silicone, caulk, wood, paint, black light](http://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/LOZANO_02-385x620.jpg)

LMF: Let’s talk about your online presence. CTRL+W33D (Caution: explicit content!) is really unusual and funny for an art project.

IL: The Internet’s endless ocean of signs, images, texts and ephemera easily disconnects material from its context. While there is a positive democratizing aspect to this, the other side of the coin is that we don’t know what things “mean” anymore. This is where most of the humor comes in for CTRL+W33D. Camp is our main tool. It comes from recognizing the slippages in the meaning and context of the images we appropriate. Camp is a “heroic” gesture that rescues the digital image from the purgatory of kitsch, of “poor taste.” As Pierre Bourdieu explained, taste has to do with economic resources and cultural capital. “Taste” is a hegemonical tool, a top-down consensus. The “heroism” of Camp humor comes from a refusal to accept kitsch and from an active re-inscribing of context and meaning. As crass as CTRL+W33D might sometimes be, it’s a moral crassness.

LMF: How did IMAGE FILE PRESS begin?

IL: I started IMAGE FILE PRESS after seeing how Hurricane Sandy destroyed the archives at Printed Matter. It seemed weird that, in this day and age, these things wouldn’t be digital. I decided that I could start creating an archive of art publications that perhaps in a couple of decades would be quite impressive, like Printed Matter’s. I also was thinking about alternative methods for the distribution of art. On the train home, I realized that everyone had their faces buried in some kind of mobile device. Finally, I wanted to create new networks for myself and other artists I felt I had things in common with. I think A LOT about the way that digital images work in culture, how they are understood maybe differently than images before the Internet, and what that “means.” I know I don’t have the answer to that and I know it’s a huge question, so I decided that I would enlist other people, ask other artists to help me figure it out. Each month, I ask a different artist to pick an image that sticks in their head and make seven “responses” to it. So far I’ve published four and have another one ready to go next month.

I see it as a deeply political move, asking artists to create images to counteract or respond to the images that are already in circulation. Cultural artifacts, especially images, spread and perpetuate culture in (often insidious) ways, and I think that as artists, we have a chance to sabotage/counteract/derail/reframe/talk back to images/culture.

![C___ OF THE EYE / C___ OF THE HAND [installation shot], 2012, variable](http://glasstire.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/LOZANO_04-600x488.jpg)

IL: Words are very important for me. I love exploring their etymology, seeing how their meaning or usage has changed over time. As an artist, I’ve gotten so much inspiration from seeing the path a word takes through time. It’s the same with music and images. Appropriating an image or a musical style from a different time period and seeing it/hearing it from a different angle can be a barometer for our culture. It can show some of the biases we have, some of the traps we fall into or assumptions we make about what’s “right” and what isn’t.

LMF: Last question: does the globalizing power of the internet share something with the Conquest of the New World?

IL: GOD I HOPE NOT.

Ivan LOZANO’s work will be featured in the 2013 Texas Biennial’s exhibition New and Greatest Hits: Selected Work by Texas Biennial Artists 2005-2011 at Big Medium in Austin, August 23- September 28, 2013.