Ricardo Paniagua is accustomed to stares. The 31-year-old’s presence alone intimidates many, and at the bagel shop near Highland Park where I interviewed him, the other patrons were flat-out bewildered by him. Paniagua looks the part of the mad man, and he paints like one too. A high school dropout who taught himself—with a little help from his friends—technique and art history, Paniagua’s Cool Hand Luke-style tenacity is finally paying off statewide. Beginning 2013 with a solo show at Dallas’s RE gallery + studio and a group exhibition at 500X, he will spend the rest of the year busting his ass to produce new works for a heavy slate of projects throughout Texas, including another solo show this fall at Austin’s Big Medium, new representation from Houston’s Peveto and other not-yet-announced exhibitions coming soon.

Betsy Lewis: You did not go to college.

Ricardo Paniagua: Right.

BL: Since you didn’t have opportunities through a university system, did you have a strategy for getting your work seen?

RP: I started painting for the pure joy of painting, without any informed aspect, but I started seeing exhibition fliers and became intrigued. I was like, “wow, people can make art and show it, too.” After that I kept my eye out for opportunities. I’d go to Irving Arts Center and set up in the park out there. During the Second Annual CADD Art Fair, I went across the street to these abandoned warehouses and hauled my art up on the sidewalk. When people drove out of the parking lot, I would see them laugh at me. I had such empowerment and belief in myself, for whatever reason, that it didn’t bother me that they laughed. It was hard to get people in Dallas to look at my artwork because I’m self-taught. Dallas is very academically oriented. Back to your question—no, I didn’t have a strategy; I learned the hard way.

BL: How were you surviving? Did you have a day job?

RP: When I started making art, I realized that materials were expensive. I got a warehouse job that paid $240 a week. It was back-breaking work, but I saved up enough money to buy a truck. I come from three generations of ceramic tile installers, so it was just a matter of me getting up and doing it. That slowly transitioned into making enough money to get by and make more artwork. That was my last job.

BL: Have you worked in ceramic tile artistically?

RP: I have. Ceramic tile is all about design and layout. I’ve done some pretty big floors. I plan on doing more when I can be the supervisor. I’ve become familiar with Antoni Gaudi. He’s a huge icon in creativeness with tiles, but he’s an inspiration more than an influence.

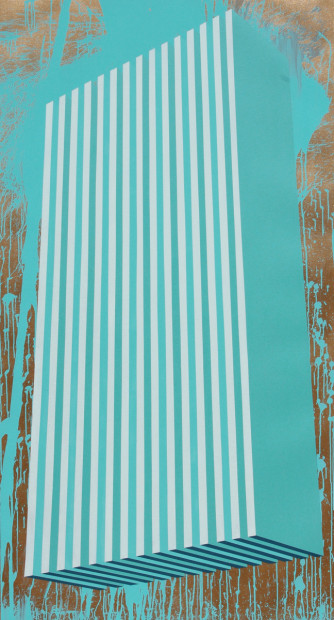

When I first started painting I was doing these narrative, naïve stories with paint, then I started getting into higher ideas with my former mentor, Michael Osbaldeston. He introduced me to a lot. I got a big job painting a mural and it forced me to learn and develop some new techniques. That’s when geometry came in, and that lay dormant; that was not representative of my studio art at the time. Several months passed before the thought came that I should incorporate this geometric idea onto canvas. It came easily, because I found myself using a lot of the same tools I used to lay out tile. As the years have gone by, it has taken over. I’ve been exploring high tolerances and op-art. I research. If I see something I’m interested in, I will definitely find out about it. The Internet is mature with art history and images, and I’ve learned a lot through some of the people I hang out with, too.

BL: What was your breakthrough in getting a gallery show?

RP: My first gallery show was in Deep Ellum, might have been like five years ago. A local photographer had a studio and also a gallery downstairs called Hal Samples Gallery. I had a lot of big, big paintings in there that are really good paintings. Not that many people came [laughs], but I gave it my all and put it out there. I was recently talking to some younger artists and they were like, “we saw your work at that show.” That really meant a lot to me—my story of not giving up is having a positive influence.

BL: What is your process for making art?

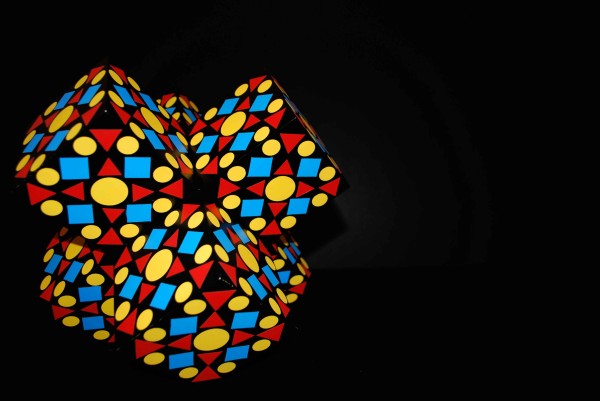

RP: Everything I start is premeditated in my head. I never do studies. A specific painting could take weeks. Some pieces could take days. Last night I did 40 abstracts on paper with graphite, household paint, artist paint and watercolor in an hour and a half. The hypercube sculptures that I was making out of wood, those damn things took like two weeks, each of them. It was ridiculous. I would start from raw wood and have to treat it, sand it, prime it, sand it, fill it with wood filler until it was seamless, flawless, pristine. I made about 30 of them in two years. I don’t miss doing them.

BL: How did Peveto find you?

RP: About four years ago I started entering a bunch of juried shows. One of the shows that I entered up until last year— haven’t been entering shows as much because I’ve been busier, which is a good thing—was the Hunting Art Prize. I got accepted into that show and one of the representatives from Peveto saw my work there and contacted me. Slowly but surely we built a relationship, and they represent me now in Houston. They’re motivated.

BL: Have you done work you consider failures?

RP: If something is an experiment and I try and it doesn’t work out, I go broke making it happen. Literally, I go fucking broke and I make people buy my artwork because I have a vision and it’s got to happen. It’s crazy. I lose sleep. I can’t let it fail because my life depends on it, and my future depends on it. If I start seeing these failures as a karmic thing and start working through them, that’s even more of an incentive to defeat them.

It’s the opposition of energetics. It has to do with breaking the physical constraints or parameters or boundaries that life presents before you. When you do that, you become innovative because you don’t let it rest. You have to make it happen.

Betsy Lewis is a Dallas writer and expert at hiding in plain sight.