When art people ask, “Where did you grow up?” and I answer, “Arkansas,” there is, invariably, an awkward pause. It is usually followed by “Oh.” or “Oh. Really?” and occasionally, “Well, um, I hear it’s really pretty there.” East coasters are the worst. It’s like they asked what your father does and you said, “He’s a serial killer.”

Now that the highly anticipated, widely discussed Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art has opened, those same people can say, “Oh, yeah, Arkansas, where that Wal Mart museum is.”

Arkansas has always had the poor, rural and ignorant stereotype – beginning with the 19th century “Arkansas Traveler” tall tales of the state’s rube squatter inhabitants. That image was given a modern face by racist demagogue Orval Faubus, who infamously used National Guard troops to prevent black students from attending Little Rock’s Central High. It seems somehow fitting that after his shameful gubernatorial career, Faubus went on to manage North Arkansas’s last great attraction, Dogpatch USA, a Li’l Abner hillbilly theme park. Souvenir corncob pipe anyone?

Like a lot of other Arkansas apologists, I hoped Bill Clinton might give us a little re-branding. I love Bill. I just wish he could have left his inner randy redneck–the one who used to pick up girls in an El Camino with a carpeted truck bed–back in Hot Springs.

And, of course, Arkansas is the cradle of Wal Mart, pretty much the most hated company in the country, if not the world. What started out in flag-waving exhortations to buy American morphed into “Let us help your company relocate to China for those ‘Always Low Prices!’” That’s before we even get into Wal Mart employee horror stories.

So you’ve got a museum, it’s in Arkansas, it’s got a name that people widely agree sounds like a meth rehab facility and it’s funded with Wal Mart’s filthy lucre. Crystal Bridges, like many of us from The Natural State, has a lot to overcome.

The same people startled by the fact that someone from Arkansas might be involved in the art world are absolutely horrified that choice works of art have disappeared into the flyover territory of the Ozarks. When Wal Mart heir Alice Walton purchased important pieces, like the Asher Durand Kindred Spirits she bought from the New York Public Library for a reported $35 million, the outcry was loud – and revealing. Michael Kimmelman, writing in The New York Times, compared the departure of Kindred Spirits to the destruction of historic Penn Station, and hoped the horror of the loss would similarly galvanize the public. FYI, Michael, nobody destroyed Kindred Spirits. It just moved. But it seemed, in Mr. Kimmelman’s estimation, that leaving the third floor of the New York Public Library for pride of place in a museum in Bentonville was a fate if not worse, then at least equivalent to, death.

And that all this was made possible by Wal Mart money was more than could be borne. Like all good liberals, I loathe Wal Mart, but let’s be fair. As an heir, Alice Walton certainly profits from Wal Mart, but she is not involved in the running of the company. And, if we are honest, good things have come out of fortunes with ethically questionable origins – didn’t robber baron Andrew Carnegie help create the New York public library system?

But I also understand that a portion of the disdain Wal Mart engenders isn’t just because brings in cheap crap from China, it’s because it brings in cheap, TACKY crap from China. Let me offer an anecdotal example. When Target moved into the hipster yuppiedom of the Houston Heights, it was essentially greeted with Cries of Hosanna. When Wal Mart announced its plans to move in as well, you would have thought an open pit nuclear waste dump had been proposed. Target brings in crap from China too, albeit better designed. And Target has had its own controversial practices, although nowhere near the level of the Wal Mart leviathan. But no one can tell me that beneath the outrage, there isn’t some hiss of socioeconomic prejudice: poor people shop at Wal Mart – poor, fat, tacky people (you’ve seen the website, right?). And all that art that Alice Walton was snatching up for her Arkansas museum would be pearls before the Wal Mart shopper swine.

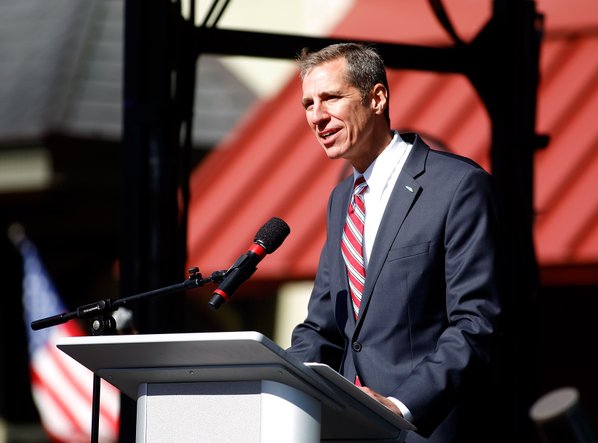

Don Bacigalupi, the director of Crystal Bridges, has his work cut out for him. I spoke with him a couple months before the museum’s opening. He was in town to give a talk at the University of Houston, where he had worked as the director of the Blaffer Gallery in the 90s. I knew him only in passing (I did some educational outreach for the Blaffer when he was there), but I remembered Bacigalupi as sharp, down-to-earth and enthusiastic about community outreach.

Bacigalupi came to Crystal Bridges from the Toledo Museum of Art, where he had helped that institution become one of the most visited museums in America per capita. Running a museum in a working class city like Toledo seems like good preparation for a museum in the Ozarks.

Although he’s an unabashed populist, Bacigalupi doesn’t believe in pandering. “The challenge in trying to be something for all those people is that you can’t simultaneously water down what you are at your core,” he explained. “You can’t lose sight of your mission at the museum, but you do have to find ways to offer points of access or open doors that allow people to begin that journey or that experience so then they might develop into regular museum goers.”

“I had a great experience in Toledo,” said Bacigalupi, as he talked with me about the efforts to foster audience participation and engagement and to “break down barriers among socioeconomic groups, levels of education, ethnic and racial lines” and his goal of “making the museum truly available and accessible for everybody.”

“It was extraordinary,” he said, “it was like one and one half times the population of the city came to the museum annually and there aren’t many other places that can boast that.”

Bacigalupi talked about the different ways people engage with a museum. He observed that some will become very invested in individual works or exhibitions or education programs, but that some will use it in other ways. He cited as an example a regular museum visitor in Toledo who told him she would come whenever she was stressed or having a bad day, saying the museum would always make her feel better and was “cheaper than aspirin.”

“Whatever use value the museum has for people, I think the museum staff has a responsibility to make that available and accessible to them,” said Bacigalupi. Crystal Bridges is free, which should make those kinds of visits possible. Although since its opening last month, it has apparently been so crowded admission is only possible through timed tickets.

I asked for examples of successful outreach in Toledo and he cited the museum’s Glass Pavilion, whose construction Bacigalupi oversaw, as prime example. The museum’s glass collection includes objects from the 17th century onward. The new building was designed to have a working glass studio at its center, which could create work that could directly relate to objects in the collection.

“Toledo is a very self-professed working class town with lots of industrial history,” explained Bacigalupi, and much of it involved glass production, often for the auto industry. “It’s in the rust belt. There were a lot of people that worked on factory lines. For them, you might think that the museum doesn’t have anything to show them, that there is no relevance there. Well that particular experience of coming to watch someone working in a kind of factory-like studio setting where they are making something with their hands related directly to a lot of people’s daily work experience. They got it that art is made similarly, not necessarily in a factory line but it is made by people with hands and talents and skills.” Then, said Bacigalupi, those same people could go into the galleries and see what everyone from 17th century masters to contemporary one did with those same techniques.

The Toledo Museum’s restaurant became another opportunity for outreach. Bacigalupi had hired a new chef and one day she had a conversation with him about food history, its preparation and meaning in different cultures, and, he said “it really reminded me of my training as an art historian and the way in which art is made in different cultures and different contexts by people with different meanings in mind.”

Approaching it as an education program, they began a series of dinners, each with a menu built around a culture or a time or a place. A wine steward would talk about wine from that place or time; a curator would discuss art from the time or place, showing related work from the collection. It became a huge success with a long waiting list. What they had initially conceived as an occasional event became a hugely popular regular feature.

“People were just clamoring for the next one and throwing ideas out about what culture they wanted to see next or eat next. It was really interesting and it taught me a lot about the way people experience art in their daily lives,” Bacigalupi explained. The fact that most people can understand food’s cultural significance became an access point for a broader cultural discussion.

He sees movies as another example of a point of access, “most people have some visual literacy around movies. They can tell you what genre it is, they can tell you what period it is, they can tell you maybe even who the director is by virtue of its style. All of these kinds of art forms in our daily lives, I think have a role in bringing people to a discussion of visual art in any context.”

But, he acknowledged, some feel pop culture plays too big a role in modern museums. “Some lament the idea that museums are including so much pop cultural material in their programming, but I think the opposite: I think there is a really strong and powerful role that pop culture artifacts and ideas can play in art museum practice and in the history of visual arts.”

“Of course,” he laughed, “I’ve written about this, my own research is all about that intersection between art and popular culture but I do think in the space of the museum there are huge opportunities for activating people’s interest and understanding of the depth that is embedded in works of art that they wouldn’t naturally get otherwise.”

Bacigalupi noted the frequent disconnect between curatorial practice and everyday life. “I think there is always tension between that kind of curatorial practice, the academic view of art and the reality of working in a museum that ostensibly is to serve a broader community. The simultaneity of curating for a very small elite educated audience and a much broader differently educated audience creates a very interesting tension and I think it’s where some of the best work comes from.

“I often talk to my curatorial staff about the need to either think about programming adjacent exhibitions that draw populist audiences and that draw refined, educated audiences; or doing them in the same space so that you have got kind of a layering of points of access” said Bacigalupi. “Audiences that might come to see a very refined and esoteric exhibition should also encounter something very popular and then the much larger audience that would attend the very popular “blockbuster” show, should also have the opportunity to encounter something that is much more focused and much more intellectually challenging.

“You can always surround difficult material with points of access.” He gives as an example “High Societies,” an exhibition organized when he was the director of the San Diego Museum of Art. What had initially been proposed as a show of a private collection of Haight-Ashbury era rock posters, became, with Bacigalupi’s urging, an exhibition that presented posters from three different time periods and brought together three different curators from three different departments. The 60s’s psychedelia was joined by works from the museum’s collection, Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters for 19th century Parisian cabarets and 18th century Japanese ukiyo-e prints with their images of the Edo district’s courtesans and performers. All were daily life, or rather night life, ephemera that had come to be valued as artwork.

“The Southern California hippie culture came out en masse for nostalgia reasons to see the psychedelic rock posters and encountered the Lautrec and the Japanese prints, and really got it.” Meanwhile, “the much more specialized audience for Japanese prints came and encountered something different that gave the work currency in today’s world. It was very interesting for those audiences to cross-pollinate. There are ways to contextualize a whole range of different materials and make them accessible while simultaneously building every audiences’ understanding of what is embedded in those works.

“The impulse for Crystal Bridges was really about reaching an audience that had been completely ignored in terms of cultural institutions, specifically visual arts,” Bacigalupi explained. “Yet there is a tremendous folk tradition of all of the arts [in Arkansas]. It’s a rich place for people to absorb all of that folk culture but without necessarily having access to other culture. Alice Walton, our founder, grew up in Bentonville and was deeply interested in art. She painted as a child. She was very eager and hungry for art and didn’t have access to it. And then when the family became successful and she was able to travel and ultimately collect art, she really lamented that she grew up without it. I think that her notion is that these are exactly the people that need it most, that want it, that hunger for it.”

Walton’s experience may sound a lot like those hardscrabble upbringing stories politicians tell for calculated effect, but I believe it. Whatever Wal Mart became, the family started modestly, living in the same sort of rural isolation and cultural privation that has pervaded Arkansas. Yes, folk culture aplenty, but the larger cultural world was hardly present. And even traveling to experience culture isn’t the same as having it down the street.

I’ve heard some glowing things about the new museum and some critical comments – mainly in terms of the architecture. But I have high hopes for its role in the region and I think Bacigalupi seems well-suited to the job. And whatever the valid and invalid criticisms of Crystal Bridges, it is an incredibly positive thing for a region that has long been culturally starved.

Being grateful, however, doesn’t mean being uncritical. This week, I’m heading home to Arkansas for Christmas. I’m going to check out Crystal Bridges for myself. (If I can wrangle a timed ticket that is.) I have to admit, Bacigalupi’s enthusiasm is contagious. As a populist myself, I’m highly susceptible.

(In January, more from my interview with Bacigalupi and observations from my Crystal Bridges visit.)

Glasstire editor Kelly Klaasmeyer is an artist and art writer who grew up in Conway, Arkansas, a city triangulated by Toad Suck, Pickles Gap and Skunk Hollow.