This wasn’t meant to be a column about art fairs—it was meant to be about wealth and conservatism—but art fairs are something I know and wealth and conservatism are major players at fairs. I can’t find the exact quote I’ve been searching for so here’s my wonky memory at work:

In either late 2008 or sometime in 2009, when all heads were still spinning at the economic meltdown, one of the curator honchos of one of the most important museums in the world attended either Frieze or Basel (Basel Basel, not Miami Basel) and then proclaimed he was “disappointed” that the exhibiting galleries didn’t bring more exciting stuff for him to peruse and, what? Actually buy it for his museum? Program it into his museum? Was that kind of thing even happening at that moment? Sure, he was probably flanked by his richest collectors-cum-board members (who were likely still so stunned by the loss of at least a third of their wealth that the blood had not yet returned to their faces). Had the work impressed the curator enough, maybe someone in his crew could still have whipped out a checkbook or put something on an exhibition agenda. But it was so unlikely in that economic climate.

Prior to the fall of 2008, art fairs had grown pretty circus-like in their ambition and wackiness, which could be kind of exciting if not exhausting. But post-meltdown, plenty of galleries were even wondering whether they could afford to do an art fair.

So his comment seemed especially tone-deaf. Why would galleries, who were fighting for their survival, bring only the work that just might—with about the same miserable chances as winning the lottery—appeal primarily to a major, cynical, seen-it-all curator, rather than to the masses they hope to actually sell to? The number of venerable non-profit institutions in the market for new and risky work is, after all, even in a healthy economy, much slimmer than the broader spectrum of spendy collectors who might take a liking to certain affordable, breadbox-sized work of art they can picture in their own house.

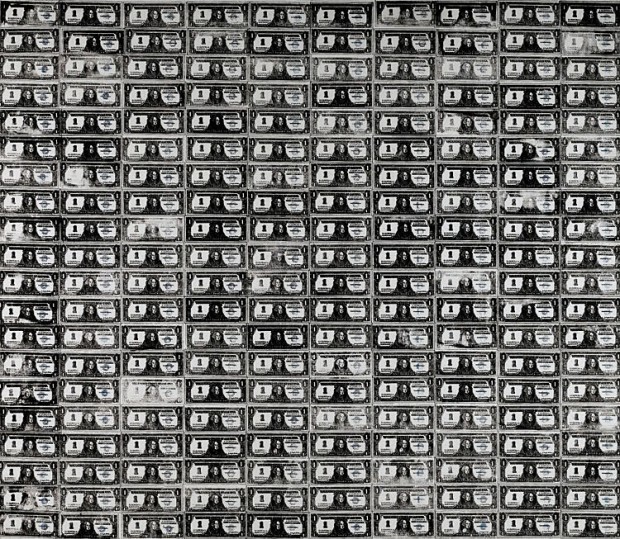

Museums, for the most part, are now slaves to their board members, and board members are wealthy. Wealth generally leads to conservatism. In other words, being really rich means you’ve got something to lose, so in most cases, wealth protects itself. This attitude can permeate museums and make them more risk averse than they should be. This of course isn’t at all limited to the art world: We’re seeing the consequences of this phenomenon across the socio-political landscape. Corporations are pretty much running the world now, through lobbies, through election donations, through policy shaping in our universities and on and on. (The effect of this on art is a profound and amazing subject. I’ll attempt, like other writers, to tackle it in subsequent columns.)

So for any collecting non-profit, no matter how known it is for taking risks, there’s still a board and a buying committee and a consensus that must be reached to go ahead with an exhibition or purchase, and everyone these days (seriously, everyone) is still watching their accounts. The recession may be boring by now, but it isn’t over.

Right now, I would never walk into an art fair expecting to see the most daring work being made today. (If you want to see daring, go to a gallery in its off season, when big sales aren’t expected, or go see what your local art collectives or co-ops are up to, where sales still aren’t as important as intent.) Sure, most major art fairs sponsor some large featured installation by one or two brand-name artists, and that work can leave an impression, but from booth to booth, I fully expect to see the most saleable work available. Saleable doesn’t equal bad. It equals desirable, and gettable, and generally safe. Charming is a word that comes to mind. As we all know by now, even the artists are making work for art fairs—works that somehow do okay while squeezed into a too-small space amid a ton of other pieces by a ton of other artists which is all within a vast marketplace that’s loud and crowded and overwhelming to most viewers. “Take me home” is the message of this artwork. “I am affordable, easy on the eyes and personal philosophy and I would look fabulous in your dining room.”

Even dedicated contemporary galleries are currently depending on the secondary market sales of works by proven modern masters. Or, if they’re not as lucky but more newsworthy, they show proven masters who are still alive (making it primary market, which is good for artists and not as good for the dealer), though this is rare. When a famous New York gallery with some of the greatest younger artists working today dedicates its entire fair booth to Ellsworth Kelly, that kind of sums up the current environment. After all, who doesn’t love Ellsworth Kelly? And more to the point, who thinks buying a Kelly would be a big investment mistake? No one. Not even a museum’s wary board member.

At the new Houston Fine Art Fair, just as has happened in the new-ish Dallas Art Fair, you should expect to see galleries bring out their greatest hits. Expect to see more of what has been selling (or at least nearly selling) in their galleries over the last year. Expect to be reassured by the sight of familiar names doing what they do best. Some upstart or visiting gallery will pull out the stops and attempt something non-commercial and unfamiliar and strange (and maybe wonderful), sure, and you’ll get a kick out of it. But that gallery probably won’t sell much of anything. They’re sort of unwittingly taking a hit for the team.

So, in other words, go, enjoy yourselves, let it wash over you like a great old tune by the Rolling Stones, and if you can possibly let yourself fall in love with one of the charmers on show, please, please buy it.

_________________

Christina Rees was an editor at The Met and D Magazine, a full-time art and music critic at the Dallas Observer, and has covered art and music for the Village Voice and other publications. She was until recently the owner and director of Road Agent gallery in Dallas. Rees is now the Curator of Fort Worth Contemporary Arts, TCU.