(To read Arthouse and the Dallas Contemporary: Crunching the Numbers, Part I, click here.)

In 2009, the Austin Museum of Art (AMOA) cancelled its plans for a new building downtown for the third time. Last December, AMOA sold the land on which it had been planning to build and in February it announced it would shut the doors of its downtown Congress Avenue location. Dana Friis-Hansen, the museum’s director since 2002, stepped down. Then, also in Austin, Arthouse laid off its curator and announced a major budget shortfall and the The Blanton Museum of Art’s director Ned Rifkin, who had been at the organization for two years, stepped down. (Meanwhile in Houston, the journal ArtLies shut down due to lack of funding.) People are not only wondering what went wrong but also how we can build more stable art institutions the next time around.

In the wake of so much turmoil in the Texas art world, this series looks at the finances of a few Texas museums. For each article, I comb through the 990s of Texas art institutions between 2004 and 2009 and try to make sense of their finances. I’m reconstructing a story from numbers filed with the IRS, so take all my data and conclusions with a grain of salt. Should my analysis need correction by someone with more intimate knowledge of the organizations, I would welcome it. The first article in the series considered Arthouse and the Dallas Contemporary alongside the San Jose ICA. Here, I discuss AMOA and use the Tucson Museum of Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art Jacksonville as comparison cases. In the third and final article, I’ll look at the Contemporary Art Museum of Houston alongside the Museum of Contemporary Art St. Louis and the Contemporary Art Center New Orleans.

If Arthouse and AMOA merge (negotiations for such a merger were announced in the Statesman on May 26), the resulting organization will be have assets of somewhere around $40 or $50 million. That’s the size of Los Angeles’ MOCA, but without the collection to match. The non-collecting Aldrich Contemporary might be the most apt comparison to the potential Arthouse-AMOA museum; it doesn’t have the huge building and collection that distinguish most other museums. What the newly formed institution would do with its resources remains to be explained. Education—including the art school at Laguna Gloria—has been equally if not more important than exhibitions to AMOA’s mission, and the production and exhibition of really new artwork has been mostly limited to its underfunded New Art in Austin triennial. Arthouse, on the other hand, has focused on exhibiting new work by international and emerging artists. Its small education programs focus on teens, the demographic least served by AMOA’s programs. In addition, the “publics” to which the two organizations have catered has been completely different over the past decade. AMOA’s public has been primarily regional, even local and primarily families. Arthouse’s public has been “the art world” (artists, curators, collectors and arts supporters) state-wide and nationally. I guess if the new organization were to meet half way between where AMOA and Arthouse are now, it would exhibit not-too-contemporary contemporary art and cater primarily to a state-wide audience.

Before Arthouse and AMOA take the plunge, this article and my previous look at their financial performance shed light on what got them into this situation in the first place and make us think about how we can prevent the mistakes of the past.

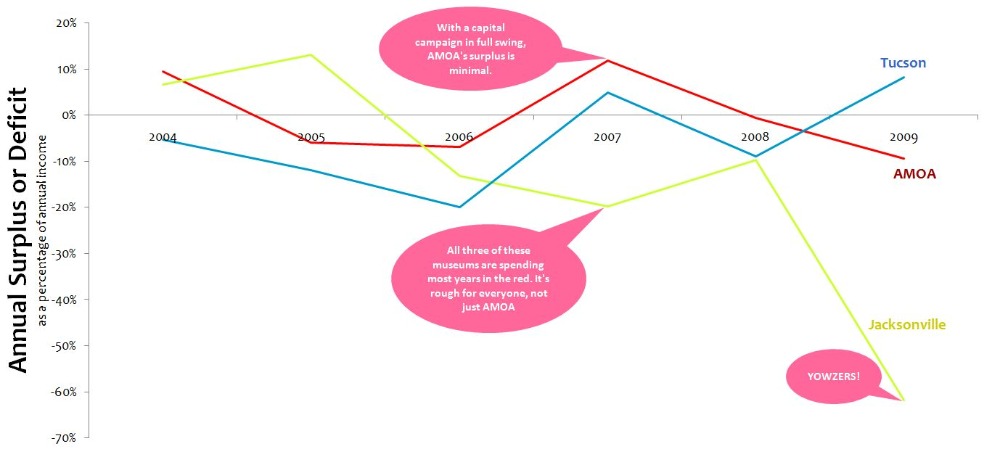

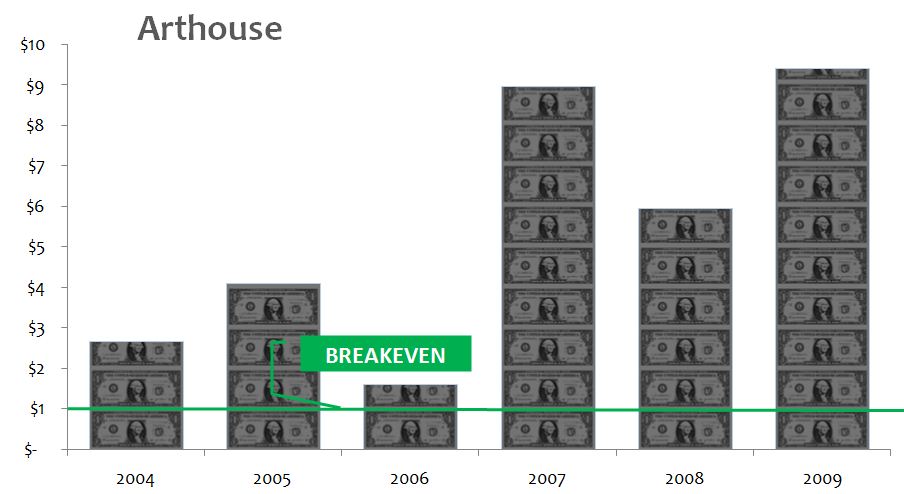

After rummaging through the financials of all kinds of museums and arts organizations nationally, I can say one thing for certain: Almost everyone was scrambling to make ends meet throughout the 2000s. As we saw with Arthouse, capital campaigns for renovations and expansion provide brief moments of relief, but after they’re over, organizations often find themselves running deficits equal or greater than those that came before. AMOA, the Tucson Museum of Art and MOCA Jacksonville are the rule rather than the exception here. (By the way, I chose these institutions because they are in cities of a similar size and they didn’t undertake any major capital campaigns during the period, though Jacksonville was just finishing one up in ’04. Both museums are slightly smaller than AMOA in terms of assets.) Figure 1 below shows annual surplus or deficit for each institution.

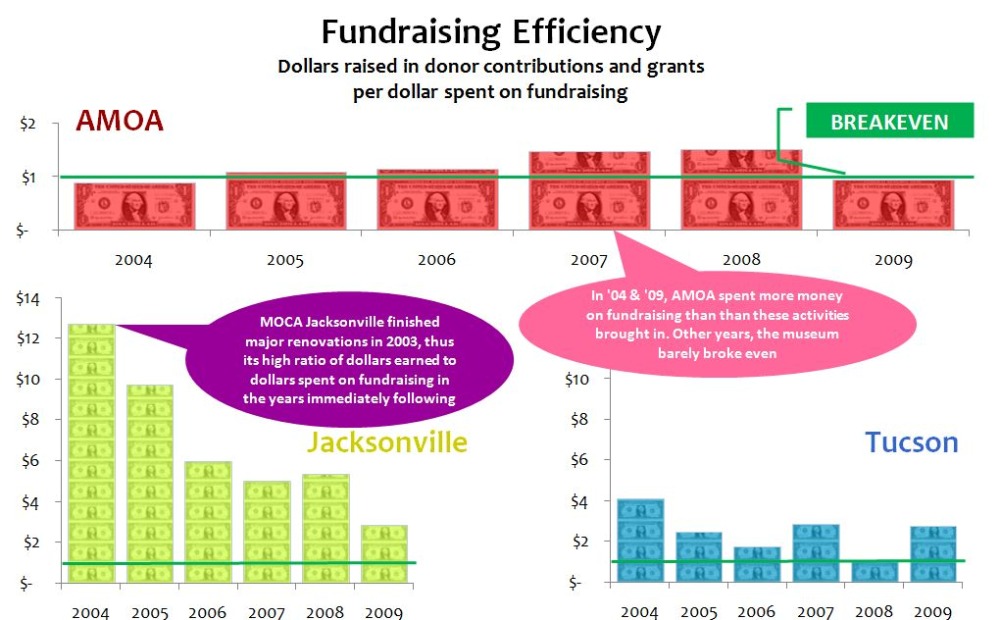

AMOA looks no worse than many other art museums on a surplus/deficit basis. However, it really has had quite a bit more trouble raising money than other institutions, as the next figure shows. The graphs show dollars raised per dollar spent on fundraising.

Figure 2 is rather terrifying. Gifts and grants to AMOA have barely covered its fundraising expenses for quite a long time. Instead, other sources of income—income AMOA from “programs,” which include rental fees for its Laguna-Gloria grounds for private events as well as art school course fees, income it got from renting out the land it owned downtown as a parking lot (I think), and, to a lesser extent, income from its endowment—have been keeping it afloat.

Why couldn’t AMOA raise money more effectively, even for its new building? Arthouse managed to do it.

Some possible explanations for AMOA’s ineffective fundraising activities include:

- AMOA lost credibility for its expansion after its first two failures to launch. A third attempt was ill-advised from the beginning.

- Arthouse had already gotten a head start on securing the donor dollars for which AMOA was competing. (Then again, for the most part, the two institutions attracted very different sets of donors.)

- Donors did not find AMOA’s mission and programming compelling.

- Donors made promises to give to the campaign for AMOA’s new building that were never realized because AMOA was compelled to cancel the project.

No matter what the case, it is upsetting that AMOA didn’t rethink its strategy regarding both general fundraising and capital campaign giving when its strategy hadn’t been working for so long already.

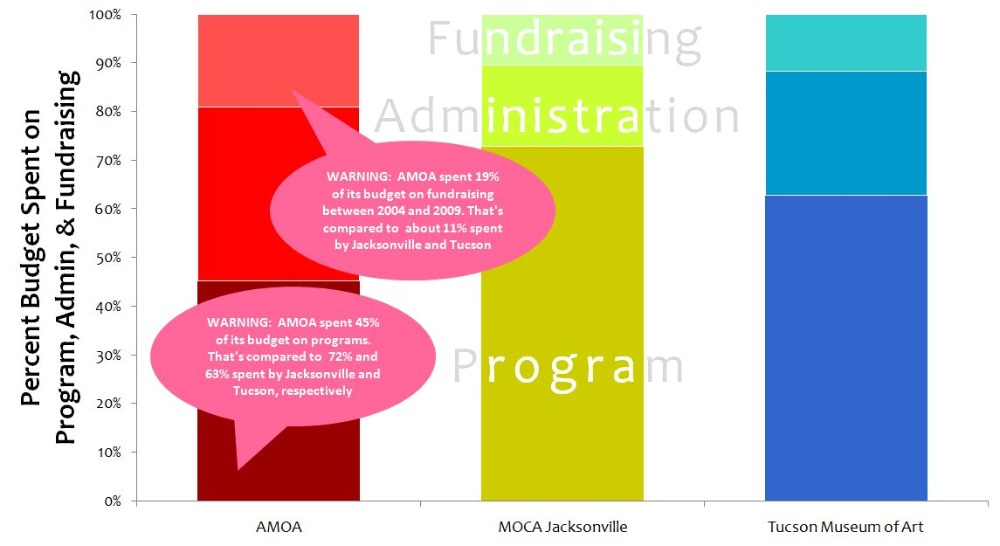

Now that I’ve touched upon income streams, I’ll turn to expenses and budgets. Unfortunately, AMOA looks no better here. Figure 4 shows the breakdown of program expenses, administrative and managerial expenses and fundraising expenses.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Again, fundraising stats seem out of whack for AMOA. The museum spent about 19% of its budget on fundraising between 2004 and 2009—that’s nearly twice as large as the percent that MOCA Jacksonville and the Tucson Museum of Art spent on the same. Even more concerning is the proportion of AMOA’s budget that it spent on administration—and thus didn’t spend on programs. It would take more work than I’ve done to detail the reasons for this properly, but at first glance it looks like huge professional management fees (for example, those paid to project managers for building planning) are the most significant factor here. AMOA kept planning, and they kept paying planners. I can’t help but wonder whether they were counting their chickens before they hatched; it sure looks like they weren’t raising the project funding to justify all that spending. Affecting these numbers to a lesser extent, it also looks like a somewhat larger fraction of employee salaries were allocated to “administrative expense” than at other museums. This could be merely a product of different systems of cost allocation. Or it could be that more time was spent on administration relative to programming than at other museums. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. Most museum staffs are overworked and underpaid, right? So maybe AMOA was just doing right by its people.

Ultimately, these data and those discussed in the previous article suggest that despite flaws in Arthouse’s financial management, AMOA’s financial performance has been even more disappointing. Hopefully, the sale of the downtown property signals an era of greater prudence. Most striking is AMOA’s longtime inability to raise significant money from donors. If Arthouse and AMOA were “competing for the same dollar” as Mickey Klein suggested in the Statesman article mentioned above, Arthouse was winning by leaps and bounds. This would suggest that patrons prefer Arthouse’s mission and vision. If they were not competing for the same dollar, but depended on different donor pools entirely, then Arthouse would be bringing far more to the merger-relationship in terms of future donor-dollars—that is if that donor pool transfers its commitment to the new organization.

With the boards of both organizations behind it, the merger seems incredibly likely to occur. Two struggling organizations, however, do not make one healthy one. Yes, a $25 million endowment will make a difference. At 5% per year, that’s $1.25 million in income from the endowment. That’s significant relative to the organizations’ expenses. In 2009, their combined expenses were $4.4 million. AMOA has shrunk and Arthouse has both grown and shrunk since then. In addition, the merger will be costly—lawyers, staff turnover, a decrease in productivity due to general mayhem, consultants to manage PR or strategic planning, mediators, and other unforeseen expenses. $1.25 million slips away before you know it, kind of like Arthouse’s money did only a few months ago.

My aim is not to be prescriptive here. I’m simply trying to figure out what happened. My sense is that the leadership of both organizations has little credibility among arts supporters right now. Whether you chalk it up to bad luck and the economy or to poor decisions and oversight, the distrust was palpable on my last trip to Austin. As I’ve mentioned before, transparency of process—for example, a public report on the state of both organizations, a strategic plan and a proposal regarding governing structures—could go a long way toward restoring trust. Or if confidentiality is an issue, bringing in an organization with a reputation for strengthening nonprofit finance, governance and mission-alignment (such as the Nonprofit Finance Fund) could do the trick.

A final thought on this subject. I recently heard one colleague console another about the merger, “A new DIY space like Okay Mountain will eventually arise to help fill the gap left in the Austin contemporary art world,” he said. The other replied, “Austin needs another DIY contemporary art space like it needs a hole in its head.”

I tend to agree. Spaces like Okay Mountain, Co-Lab, and Domy are wonderful. But they cannot anchor the Austin contemporary art world in the way that Arthouse has the potential to do. The loss of Arthouse would be a severe blow to the truly contemporary (emerging, experimental, risk-taking) art scene in Austin. It’s not the merger itself people are freaked out about. It’s the probability that the newly formed institution will not be a risk-taker. If the leadership could assure the community that the new organization will prioritize experimentation and politically and aesthetically challenging work, it would meet with little resistance from the artistic community. It could do this through a forward-thinking mission and vision and a carefully crafted strategic plan. The question is, will it?

*AMOA’s data come from the 990s of both The Austin Museum of Art, Inc. and The Austin Museum of Art Endowment Fund.

Claire Ruud has an M.A. in art history from The University of Texas at Austin and is pursuing an M.B.A. at The Yale University School of Management. She thinks a lot about feminism, queer theory, and financing contemporary art production.