Rebecca Carter is an artist living in Dallas whose interests include psychoanalytic theory, feminism and work with indeterminate boundaries. Since moving from Chicago in 2005 to take a position at Southern Methodist University, she has regularly visited the Rachofsky House, both with and without students, collaborating with director of education, Thomas Feulmer to teach adult continuing education courses as well as to produce the “Night of Video,” an event showcasing video work form the collection. She writes about the house’s latest transformation.

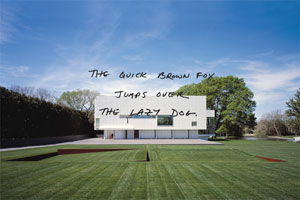

The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.: Dallas’ Rachofsky House has stored away its collection of Arte Povera, Minimalist and Post-Minimalist artworks for the summer, yielding the Richard Meier interior to a site-specific installation of text based works by the artist Ricci Albenda.

It is impossible to do with a word processor what Ricci Albenda has done with text in his paintings, though it is likely you might not notice. In Albenda’s universe, there are alphabets and wor(l)ds of color, letters, halos, periods, songs and song fragments, nonsensical maybe words and word play. Periods define end points on nearly every wor(d)k. A single exclamation point (eek!) squeaks on a red canvas.

The title of the exhibition is a key to entering Albenda’s universe. “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” is a pangram, a phrase that contains each of the letters of the alphabet at least once. This particular pangram is used to test keyboards and display fonts. Its function and meaning are more about the alphabet and machines than animals and their varying speeds or inclinations. However, its usefulness as a tool relies on how its narrative composition functions with the subjective processes of memory and thought. Without conscious effort, it is easy to conjure up images of red foxes, sleeping dogs and vague references to secretaries. It would be very clear if a letter were missing, out of place, or otherwise malfunctioning. The title points to the way the alphabet relates to text-producing machines and how we in turn relate to these text-producing machines. This semiotic slippage is a nexus around which Albenda’s work radiates.

The painting, my machine., looms over the second floor living space. Its placement, both physically within the house and conceptually within the exhibition, makes it a cornerstone. Albenda speaks about working on this piece for an extended period of time after he knew it was sold to a patron. During the time-intensive process of painting, (he doesn’t use tools of mechanical reproduction) he became acutely aware of subtle perceptual differences between his right and left eyes. My machine. in this sense becomes a reference to the body, that tool for perception and experiencing life. In the context of this house it recalls le Corbusier’s proclamation of the house as “a machine for living” and Sol le Witt’s conceptual art in which “the idea becomes the machine that makes the work.”

This discovery of perceptual/mechanical difference between his two eyes (“I”s?) led Albenda to further investigate the phenomenon in the people. paintings – canvases with the word “people” painted on them. He made the original, people. (primary painting), with both eyes open while standing in front of the canvas. The remaining five people. paintings are painted copies. Albenda painted four of them while viewing the original from various distances with one eye open. The fifth he reproduced not by looking at the original but rather by seeing with “the mind’s eye.” Upon close observation the resulting paintings reveal subtle variations, the curving of straight lines, or shifting of tilts. Albenda is a highly subjective text-producing machine. We all are.

The people. paintings line the walls of the hallway when you first walk into the exhibition. During the previous installation of the permanent collection, there was a tightness and a slowness to this space. A Richard Serra lead piece leaned up against the east wall across from a Robert Irwin disk. The spatial organization mediated the speed of the visitors’ experience, something I experienced several times in various circumstances. An entire group of people would stand at one side of the narrowed corridor waiting to move single file through the passageway, with director of education, Thomas Feulmer carefully monitoring their every step. There was an element of anxiety involved with the process. One false step and the heavy lead could slip and damage the visitor, the work, or the house. Over the course of the installation, the Serra piece disappeared, leaving the space open to a more relaxed flow. The people. paintings similarly modulate a tension related to speed and space. On one level, it is easy to read them quickly: people. people. people., a multiplicity, crowds, perhaps, those same people whom I had watched march single file past the Serra. On the other hand this work is extremely slow; it is slow to reveal itself and slow in the intangible space/time of its production.

The exhibition seems sparse, but is richly associative. Words and phrases and canvas depths push and pull time and space within the house, between the works and in the mind/body of the viewer. There are constellations, things that build, connect and disconnect. Already a buoyant and light filled object on its dark granite plinth that extends outward in every direction, the Richard Meier house floats differently with this work. It becomes lighter and the color of light is more present. Blue sky and green grass appear as reflections on walls in a fluid interplay between exterior and interior, all the more visible against the subdued rainbow of black and white paintings in the central space.

Garden hangs on the south wall of the library. Latin names of plants from Albenda’s garden in Brooklyn extend across green canvasses of varying shades, sizes and dimensions. The letters of the names are in grayed green hues of his "COLOR-I-ME TRY"color-mapped alphabet, a system where each letter is assigned a color to contribute another level of visual rhythm to the text. Formally the canvasses move forward and backward in space, extending out towards the squared magnolia hedge visible through the library window. The modulating color of the text vibrates in relation to the light moving over the individual leaves. There is an interplay here between the cool presentation of Garden as Latin text on canvas, the intimacy of the private and personally tended thing it references and the meticulously and mechanically groomed landscape of the Rachofsky house.

Albenda’s The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. contains pieces by the artist from the past nineteen years. It verges on being more a highly considered retrospective than a truly site-specific installation, but under scrutiny the work and work/site relationship remain dynamic. It is an exciting development in the house’s evolving life and hopefully this is not the last time we see a single-artist project here of this ambition, scope and generosity.

Ricci Albenda: The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.

The Rachofsky House

Dallas, Texas

Exhibition available for viewing by appointment through July 31.