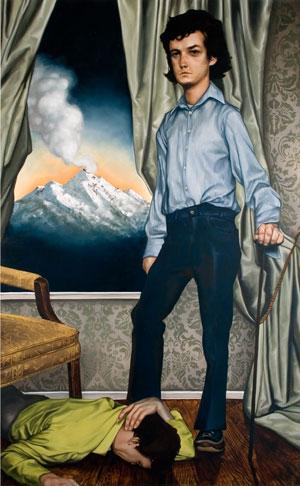

Standing Man with Dead Man and Volcano is Alverson’s best. A man in a striped shirt stands over the body of a similar man in a green shirt in a small room. Hovering over the scene out the window is a picturesque, snowy volcano. Stories come crowding into one’s mind: did the standing man kill the dead man, or discover his body? He stares into space with sad puppy eyes, seemingly detached. Is he feeling guilty? Or sad? What’s the relationship between the men? Will the Volcano erupt? Like the rest of the painting, it’s quiet now, but with an implied violence underneath.

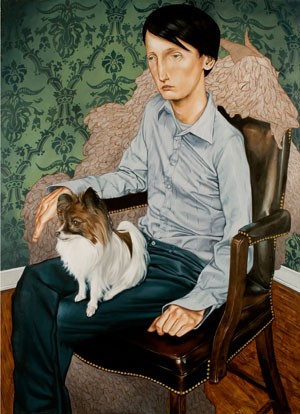

Return of Prehistory is the sequel. The standing man has been clobbered and slumps, bloodied by his own cane, in an armchair. The dead man, still dead, lies at his feet. The room itself is broken open; distant flames and a soaring pterodactyl symbolize Armageddon.

Like the traditional paintings they mimic, Alverson’s works are contrived stage sets — but subtle inconsistencies in the lighting, the proportions of the bodies, and the painting style give them an eerie tension. Alverson is a jack of all painting styles, and master of some. Stiff, academic figure painting, fluid, lustrous drapery, mechanical stenciling and wood graining, and cheesy palette knife work on the volcano make his pieces into a patchwork of painterly effects. While this assures him some postmodern credibility, and adds a tad to the paintings’ overall oddness, more often it’s a distraction. The real strength of these two paintings isn’t the Po-Mo deconstruction of style, but the atmospheric, surrealist storytelling: there’s a very curious and subtle play between the standing man’s foot and the dead man’s hand, which overlap, seemingly by accident. There’s a moment of confusion where the standing man seems to have placed one apelike bare foot on the dead man’s head.

The same strengths and weaknesses go right around the room. Alverson’s intricate drawings occasionally strike an evocative chord but more often dissolve into fruitless, albeit fluent, embellishment. Alverson is better at creating single images than tableaux. The pop-eyed shark, the swimming goat’s head, the hovering coffins, and plump, penile toadstools are lively characters trapped in dull, obscure scenes. It’s doodle art — Alverson knows how to draw things, but doesn’t know what to do with them afterwards, placing several objects on a page and filling the empty space with nifty textures.

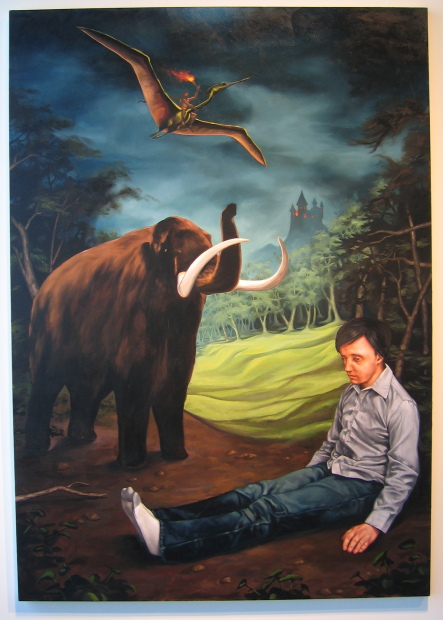

Paintings like Sitting Man with Mastodon and Pterodactyl have the same problem. On a road through wooded countryside sits a dejected-looking man in blue jeans. A few yards down the road is a shaggy mastodon. Alverson places them together in a wooded scene as if they were in an automobile showroom or a natural history museum; nothing’s happening or about to happen, they’re not even looking at one another. Overhead, there’s a little more action: a caveman holding a flaming torch rides the neck of a pterodactyl. Apparently he has set fire to the burning castle in the distance, but his connection to the mastodon and man in the foreground is obscure. It’s possible to imagine stories, but it’s an effort. Unlike Standing Man with Dead Man and Volcano and Return of Prehistory, you are not anxious to know more.

Castles, caveman, dinosaurs, armed nudes, a goatherd: Alverson’s lesser paintings draw their imagery from the fairy-story world of historical painting and children’s literature. That’s not in itself bad, but Alverson is content to refer to those familiar images without re-inventing them as his own. In Pile of Bodies, a standing nude in a loincloth and helmet stabs his sword into a pile of bloodless body parts; his long, biblical beard twists towards the peak of a snowy mountain in the distance. He’s a poorly painted, cardboard cutout of a Frank Frazetta character, lit with a rosy, heroic spotlight. Alverson captures the campy swashbuckling of Jacques Louis David’s Sabine Women (from which the main figure is drawn), not realizing it was campy swashbuckling in the first place. He’s aiming for the same over-the-top blood-and-guts silliness, but lacking David’s sincerity, he doesn’t put his heart into it. The Sabine Women measures a titanic 13 x 17 feet. Now that’s funny.

It’s dangerous, quoting the masters. Alverson’s figures need to be better, or worse. As is, they’re struggling to be good in the traditional manner and failing, yet not screwy enough, or in the right way, to be interesting as intentionally bad painting.

Thunderdome is a rocky road, full of promise and pitfalls. The show is an eclectic collection of different approaches: elaborate decorative drawings, sorry figure painting, some portraits, some fairytales, some comix. Alverson is figuring out what to do with the impressive skills he’s got, and, judging by the best work, he might get somewhere.

Images courtesy Lawndale Art Center

Bill Davenport is an artist and writer living in Houston. He was the first contributor to Glasstire.